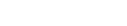

Poetry is an art of great particularity, surrounded by an aura that makes the world of poets seem mysterious and intriguing. However, the poet, like any human being, needs appreciation and support from others to progress and continue. With the ongoing changes and developments in Korean poetry, it has become necessary to view and understand this world from the perspective of contemporary poets and to keep pace with the rules they live by. In this article, we meet the poet Jo Hae Ju, a contemporary poet who began her career in 2019 and has published two poetry collections so far, yet has already gained significant attention in contemporary literary circles. She recently published an article in the Winter issue of Korean Literature Now magazine titled “Becoming a Poet,” in which she spoke candidly about the difficulties faced by young writers in Korea in gaining opportunities. Through this interview, the poet shares her artistic philosophy and her definition of the essence of poetry.

The interview was conducted via email from January 1 to January 9.

Could you tell us more about your beginnings? What motivated you to become a poet?

I began writing poetry around my second year of high school. I had a vague dream of becoming a writer, so I enrolled in a specialized high school in the creative writing department. However, I did not enter the department with the intention of becoming a poet from the start, to the extent that I applied for the entrance exam by writing a short story rather than a poem. Even until the end of my first year, there was no decisive reason or specific moment that made me fall in love with poetry. But one day, when I looked at the bookshelves in my room, I found them filled with thin and light books, poetry collections. At that moment, I suddenly realized that I had already loved poetry. It was a belated realization, as if I had reached a point of no return.

As my love for reading poetry grew, I simultaneously began to enjoy writing it. As I continued writing, a desire arose for someone to read my poems—in other words, I wanted to become a poet. I believe that one important aspect of a child’s transition into adulthood is gradually coming to know oneself: who one is and what one loves. Through poetry, I discovered that I am a person who loves blank spaces, loves multiple and endlessly diverse sounds, and loves the way that paper alone, and sometimes sound alone, can lightly float through the world, as well as that sense of ambiguity that can never be fully grasped, no matter how many times one rereads a poem. Through poetry, I realized that I am someone who loves all these things.

In your recent article for Korean Literature Now, you speak about what it means to truly “become” a poet.

Do you think being called a poet is something granted by others, or something one must claim for oneself?

For those who view the poet as a romantic being, akin to a traveler or wanderer, the statement “a poet is someone who declares themselves to exist” may sound more convincing. However, I do not think the title “poet” is very different from the title “human being.” When I consider which of the two options might be better for those who wish to be called poets, I ultimately find myself leaning toward the idea that a poet is someone who is granted that title by others.

Recently, the word “independent” has been used as the opposite of established institutions. If we trace the origin of this word, we find it connected to the spirit of the “independent salon” that once prevailed in Japanese art circles, where anyone was allowed to exhibit their work without review. This approach was criticized by some at the time as producing low-quality art, and the question raised was: “How can we trust works that have not undergone review and enjoy them as good works?”

In this sense, determining what constitutes “good poetry” and who is a “good poet” is itself a system and a form of authority. The poet is not a being who enjoys absolute freedom outside this authority, but rather a being who continually redraws and erases the boundaries of that authority from within it. Just as it is impossible to recognize a human being as human outside the world, a poet cannot be completely separated from recognition by others. Therefore, in the Korean context—unlike the Japanese one—the word “independent” can be understood not as an assertion of the absence of evaluation itself, but as an attempt to diversify how recognition is granted. In conclusion, while the title of poet is given by others, adopting a stance in which one declares oneself a poet can help lead to that recognition.

How has your understanding of yourself as a poet changed since your debut?

What emotional responsibility comes with calling yourself a poet?

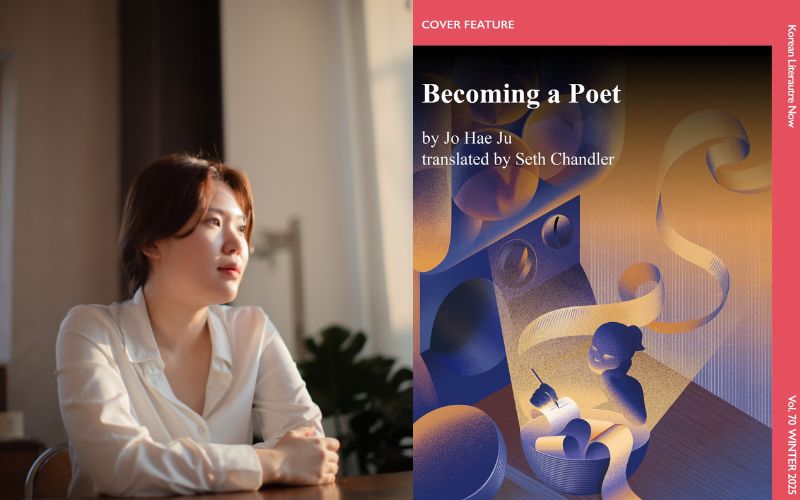

Even after my first poetry collection was published, I spent some time asking myself whether I was truly a poet. The image I had held since childhood of the “moment one becomes a poet” was a dramatic scene, such as receiving a phone call from an unknown number on a day when white snow is falling. Although I did not experience such a moment, my first collection was published in the middle of winter, with a white cover like snow. After that, as time passed and many people began calling me a “poet,” and as the snow gradually melted, the title became natural and no longer embarrassing to me.

As for the change I felt within myself, it was that I began trying to write in a way that was “stranger” than before. In the past, I worried that readers might not understand my intention, but now I have freed myself from that concern and try to write according to my own truth. When a person is truly honest, they inevitably become a little strange.

Do you prefer waiting for inspiration, or do you tend to plan carefully? Do you have a specific routine for writing?

In fact, I am not a planner at all, to the extent that having a routine has become a goal in itself. All I do is write down an emotional knot when it forms within me and then leave it there. If one must speak of a routine, perhaps it could be said that, unlike other literary genres, I try to minimize the time I spend sitting at a desk when writing poetry.

If we imagine a rice-cake-making machine at a mill, rice dough is placed at the top and comes out below as a long rice cake; my working method is similar. I place the idea of the poem in my mind like dough and let it mature while I am busy with the various activities of daily life. I think as much as possible away from the desk, and when I finally sit down, I write very quickly.

Among your works, what do you feel represents you the most and why? Also, could you share with us the writing process and what motivated you to write it?

It is very difficult to choose a single work. I cannot say that one poem is more complete or distinctive than others, but I would like to mention the oldest poem in my first collection. It is a poem titled “The Birth of a Pebble.” I wrote it when I was twenty-one years old, in my second year of university. When I reread it today, I remember myself in my early twenties, rolling through the world without protection, full of anxiety.

How did rejection shape your relationship with writing?

Do you remember your first rejection letter, and how it made you feel?

In truth, I do not remember at all the moment when I received my first rejection. I once read a phrase that said, “Over time, only the process remains in memory, not the result,” and I found this to be very true.

If I were to compare the feeling of rejection, it would be like throwing a pebble down a cliff whose depth is unknown. Sadness was not the strongest emotion; rather, it was the emptiness produced by the absence of any reaction.

What would you like to tell young writers who are currently doubting themselves?

What does continuing to write mean to you, beyond recognition, publication, or the title of “poet”?

In reality, what a person who doubts themselves needs most is recognition from others, and for that reason, no other words may easily reach them. Still, if something must be said, it would be this: my teacher, the poet Kim Eon, once said, “If you write one hundred poems, something good will happen.” I would add to that: “If you read one hundred poetry collections, you will clearly see what kind of poet you are.”

For me, writing poetry is no different from living itself. Poetry is a way of life. Even in my interactions with people, I try to treat them as I would read a poem. Others cannot be fully understood or predicted, and for that very reason, they sometimes affect me much more deeply than I expect.

Who are your favorite poets in the contemporary poetry scene in Korea? And how did Korean poetry evolve and change in the last few years from your point of view?

It is rare to find a country with such a wide range of poets with diverse and distinctive personalities as Korea, which makes it very difficult to choose just one or two names. I read with affection the works of Lee So-myeong, Hwang In-chan, Kim Eon, Kang Seong-eun, Kim Hye-naeng-seok, Kim Bok-hee, Kim Yun-deok, Im Seong-yu, Lee Si-hee, Kim So-yeon, and Hwang Yu-won.

Looking at the trajectory of Korean poetry in recent years, I feel that visual imagery has become less pronounced than before. When I first studied poetry, I was taught that a poem should leave a clear image in the reader’s mind after reading it. Now, however, there seem to be more poems that reveal the poet’s own nature through narrative expressions closer to prose. It is as if the focus has shifted from constructing images to the flow of inner confession or stance through the sentence itself.

What are your upcoming plans?

Until recently, I was busy completing my doctoral dissertation. My research examines the “nomination” system used by the magazine Modern Literature in the 1960s, through which I sought to highlight the pivotal role played by “aspiring poets” in advancing literary history. The dissertation is expected to be available in March or April on the RISS website, and I would be very grateful if it were read.

Last year, I signed several contracts for essay collections, so this year I plan to focus seriously on prose writing. Of course, I will not neglect writing poems for my delayed third poetry collection. The prose works to be published soon will likely include a travel book, texts on “solitude,” and diaries recording my daily life as a poet. I hope readers will take an interest in them.

There are notable developments taking place in the Korean poetry scene, and due to the difficulty of the language, bringing Korean poetry to the world is a challenging task. However, through the efforts of serious and sincere poetic voices such as Jo Hae Ju, Korean poetry will undoubtedly continue to progress and, over time, receive the attention it deserves.

Keywords:

Korean poetry, Korean literature, Jo Hae Ju, Korean Literature Now, Korea.net, Republic of Korea

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0