Pierre Bissou is a French publisher and translator specializing in literary translation, and he has played an important role in introducing Korean literature to French readers through his translations of many works in partnership with Korean translator Choi Kyung Ran. He developed a unique translation method called the "Four Hands" approach in collaboration with Choi Kyung Ran and translated important works by several authors, including Han Kang and Kim Un Su. He recently published an article on some aspects of his career in Korean Literature Now, Winter issue. In this article, we will learn more about his translation style and how his background as a publisher influences his translation work.

The interview was conducted via Gmail from January 1 to January 6.

Can you tell us about your early life and what first drew you to literature?

My father was a great reader, even though his profession was very far removed from that passion. Consequently, I grew up in an environment surrounded by books. Even now, being in a place without a book within reach feels strange to me; I bring books back from everywhere, even if I cannot read them because I don't speak the language.

How did you initially get involved in publishing and editing?

During my studies, I worked for a few months in a bookstore and then for two years in a public administration that assisted booksellers and literary associations. Through this, I met a group of people who were starting a literary magazine. We got along well, and I joined their team. A few years later, the magazine became a publishing house, Le Serpent à Plumes. That is how I became a publisher, without formal training, guided simply by my passion.

What motivated you to start working with Korean literature?

At the time, I lived in a small house in the Montparnasse district of Paris, and almost everyone in the buildings surrounding my courtyard was a Korean student. The landlord had found these students from Korea to be very serious, and gradually they co-opted one another until they made up three-quarters of the tenants. It so happened that the person living on the ground floor in an apartment overlooking my courtyard was Choi Kyungran, a Korean translator. Since the landlord knew we were both in the book industry, he introduced us. Thirty years later, we are still working together!

How did your background as a publisher influence your approach to translation?

I believe it was fundamental. Since I don't speak Korean, my entire job consists of understanding the text via a "basic" translation and projecting it into a French language that respects its style, intentions, and mechanics. As a publisher, I trained myself in this objective reading of a text, but I also developed, it seems to me, a particular sensitivity to perceiving the author's desire. When you are a publisher, you can read a text in two ways: either by asking yourself what the readers will think of it, or by asking yourself what the author wants to achieve. This second approach has always been mine, and I believe it is invaluable to me today in this partially "blind" translation process.

Can you describe your “four hands” translation process in detail? How do you divide work with your Korean-language partner during translation?

Our method is well-oiled by now. Choi Kyungran reads the text and tells me about it—to explain the story, of course, but primarily to provide context and give me an idea of the style by comparing it to other texts. Then, she produces an initial translation from Korean into French. This is already an active translation in which she watches out for repetitions (a recurring issue between our two languages), verb tenses, and, crucially, the overall comprehension of the text, because later it would be difficult for me to detect possible misinterpretations. Once that is done, she sends me her translation. I place her file on the right of my screen and open a new blank file on the left. It is essential that I completely rewrite the translation to achieve a unified and coherent work. I don't "correct" her version; I write a new one based on hers. Finally, when I finish, we begin a cycle, which can be quite long in some cases, of cross-reading and exchange. Sometimes she tells me I’ve strayed too far from the original and must correct it; other times, I tell her that a certain phrasing or expression isn't quite right and that we should use a different solution to convey the author's intent. When we are finally satisfied with our work, we send it to the publisher

.

How has your understanding of Korean culture evolved over time?

I visited Korea for the first time in 2013. I returned briefly in 2023, then spent two months there in 2024, mostly in Bucheon. I have just returned from another month-long stay in Gwangju (to discover the locations of Human Acts, the Han Kang novel I published in France back in 2016) and Seoul. This time spent on the ground is the most precious; it feeds me with all the details you cannot learn from books. Furthermore, I have maintained many contacts with Korean authors, and their company is a great help in grasping Korean culture. Then there are my readings, visiting Korean exhibitions in France, and the many events I participate in here, not to mention the Korean restaurants in Paris that I frequent with great pleasure! Everything contributes to this internal "infusion" of the other's culture, but it is true that one learns the most by traveling and exchanging directly with people.

What challenges did you face when you began working with Korean texts?

Understanding the author's desire of the author. That is the crucial point. Once you have grasped the intention, you can enter the text with the author. At least, that is how I feel things.

How do you preserve the author’s voice in translation?

As I mentioned, I try to grasp their intention so that their voice resonates within me. Besides my own way of progressing through the text, I have the constant, vigilant oversight of Choi Kyungran, who prevents me from wandering into faulty interpretations. In this regard, I believe years of work have steadily improved this mutual exchange. I must admit that when we started, we frequently opposed each other fiercely on certain points! Today, our practice of one another is much more intuitive.

When translating, what is most important to you: rhythm, accuracy, or literary style?

Ideally, we never choose; everything should be respected simultaneously. That is the challenge of translation. But of course, one must constantly arbitrate between the elements that make up each book. For our part, I think it happens quite naturally. The text guides us. Additionally, you have to understand that we work for publishers who have their own vision of the final translated text, even though they may not have the means to know the original. Publishers might ask for more of this or that—that the text be polished for better understanding by a French audience. Sometimes, publishers want a text that is rigorously "French" in form, whereas Choi Kyungran and I prefer a slight "Koreanism" to let the original language be heard, marking a minimal difference between a text written by a French person and a translated text.

What has it been like translating Han Kang’s work?

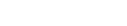

Translating Han Kang has been a great, marvelous undertaking. I had the joy of being Han Kang's publisher for four of her novels: The Vegetarian, Human Acts, Greek Lessons, and The White Book. When I lost my publishing house, Le Serpent à Plumes, I also lost my authors, including Han Kang. So when Grasset later entrusted us with the translation of We Do Not Part, it was a great joy to be reunited with Han Kang and her fascinating literary universe. Furthermore, translation offers a different approach to the text, more technical, if I may put it that way. This allowed me to further enrich my perception of Han Kang's work.

Can you share an example of a particularly challenging passage you translated?

From a practical standpoint, Korean has a variety of ideophones to describe snow, which bring a poetic nuance that doesn't really exist in French, where the vocabulary around snow is more technical. We had to deal with dozens of pages filled with snow! In those cases, you have to try to balance repetitions and metaphors with great tact, without overdoing it in either direction. It was a very delicate exercise. I hope we found the right way. We also spent quite a bit of time on a symbolically important scene where the narrator arrives at a crossroads at night, in the snow, and... well, I won't say too much for your readers who haven't read the book yet, but we had to try to both understand this somewhat encrypted moment and, at the same time, preserve its complexity—not making it entirely transparent either. It was absolutely fascinating.

Among your translated works, what is the closest to your heart and why?

It is undoubtedly We Do Not Part because of that reunion with Han Kang. But I also took great pleasure in working on Cho Nam-joo, Kim Hye-jin, and Kim Un-su, of course, who have become true friends.

How do you think translation can connect the different cultures?

Translation is an essential source for sharing cultures. For instance, Naguib Mahfouz is translated into Korean and published by prestigious houses like Munhakdongne and Minumsa. Translation invites you to discover the world and allows you to open your mind to difference. One detail I find telling: in translating from Korean to French, I know we always have difficulty grasping humor. Koreans don't laugh at the same things as the French. Egyptians don't either, I imagine! Just that, learning to understand the laughter of the other, is an incomparable joy.

.

What is your advice to beginners in Korean?

Eat Korean! And enjoy yourself. It will be an excellent way to train your mind for difference and wonder. (Obviously, you will also need to read Korean authors, discover Buddhism, take an interest in the geography of the Korean peninsula, listen to Korean jazz or K-pop, try ginseng beauty masks, or spend a few hours on dramas. But start with a little kimchi.

What are your upcoming plans?

Today, I am starting a new translation that Choi Kyungran sent me this morning. It’s a crime novel. Just before this, we finished a Korean science fiction book, a genre that is very popular these days. We also just turned in a collection of short stories by Cho Nam-joo, which was absolutely exhilarating. Korean literature is very diverse; between Han Kang and "Healing Books," the range of flavors is incredibly rich.

Translation is the most important means to unite people; you cannot communicate sincerely with a nation without understanding its language. Despite the fundamental differences between French and Korean and the difficulty of learning the language, publisher and translator Pierre Bissou developed an effective method to publish Korean works in French, driven by his passion for Korean literature and culture, inspiring anyone aiming to work in the literary field.

Keywords:

Han Kang, literary translation, Korean Literature Now magazine, Korean literature, Pierre Bissou, Korea.net, Republic of Korea

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0