December is often a time for reflection — a moment to take stock of what has been, and to look ahead to what is still to come. Literature is one of the most enduring ways cultural heritage travels. Through translation, reading practices, and shared reflection — particularly at the end of the year — literary exchange becomes a form of global dialogue grounded in memory, imagination, and human connection.

That reflective rhythm seems to be finding resonance beyond Korea’s borders. Over the past year, I have observed a growing number of readers in the UK engaging with Korean literature in translation. This piece looks at how that interest has expanded — through literary events, reader encounters, and shared reading practices.

When I first turned my attention to Korean literature in 2007, translated titles were few and far between. Today, I find it increasingly difficult to keep up with the number of books being published. This shift feels both gradual and unmistakable, shaped by years of translation work, sustained publishing interest, and changing reading habits. Increasingly, publishing companies are also taking chances on translated titles.

Although Korean literature had been slowly gaining momentum, one moment in particular seemed to crystallise this change. Han Kang’s Nobel Prize win in October 2024 helped propel Korean literature onto the global stage. It felt almost unexpected that this quiet, softly spoken 55-year-old woman from Gwangju would command such widespread attention with prose that is deeply poetic while confronting dark, traumatic, and at times visceral themes. Her win has brought renewed focus to Korean writing more broadly, and many South Korean authors appearing abroad now reference her work as a touchstone.

I remember first meeting Han Kang briefly in 2014, together with her translator Deborah Smith, when she visited the UK during Korea’s year as market focus at the London Book Fair. It was a short encounter, and little did we know then that the book she was promoting, The Vegetarian, would go on to have the global impact that it did. Looking back, that encounter now feels like a marker of how far Korean literature has travelled — and how much further it continues to go.

Having attended many literary events this year, both online and in person, I have noticed a shift in conversations: in the questions audiences ask, in the recommendations shared between readers, and in the curiosity around how people are discovering Korean literature — often through word of mouth, translation, and chance encounters rather than formal promotion.

Korean literature is rooted in Korea’s cultural heritage. Talking with booksellers, I’ve been struck by how strongly and consistently they speak about Korean fiction — not as a trend, but as something they genuinely value.

Over the past year, my engagement with Korean literature has taken shape through a series of encounters — often brief, often informal — that accumulated quietly over time. At literary events, bookshops, and in conversations between sessions, I found myself repeatedly speaking with readers, booksellers, translators, and writers who had arrived at Korean literature through a single translated book and were now looking for more.

In June, I met author Heijung Hur, who had travelled to the UK to promote her first translated work, Failed Summer Vacation, a collection of short stories translated by Paige Anaiyah Morris. Speaking at the Korean Cultural Centre, she reflected on the writers who had shaped her practice — Han Yujoo, Gu Byeong-mo, and Han Kang among them — and described her own writing as semi-autobiographical, a sustained interrogation of the self that functions as both reflection and reckoning.

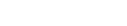

Later that summer, author Yun Ko-eun visited London to speak about Art on Fire, translated by Lizzie Buehler, at Waterstones Covent Garden. The conversation offered insight into her approach as a writer — one that uses quiet absurdity to expose the unease already embedded in everyday life, allowing humour and fear to sit uncomfortably side by side.

One moment that stayed with me took place during October Culture Month, organised in partnership with the Korean Cultural Centre and Foyles. I spoke with a reader who had carefully tabbed her copy of A Thousand Blues by Cheon Seon-ran, translated by Chi-Young Kim, marking the passages that had moved her most. She told me her journey into Korean literature had begun with Almond by Sohn Won-pyung, translated into English by Sandy Joosun Lee — a book that resonated so deeply she later sought it out again in Polish, translated by Urszula Gardner. At the same event, another reader quietly pressed a recommendation into my hands: Hunger by Choi Jin-young, translated by Soje.

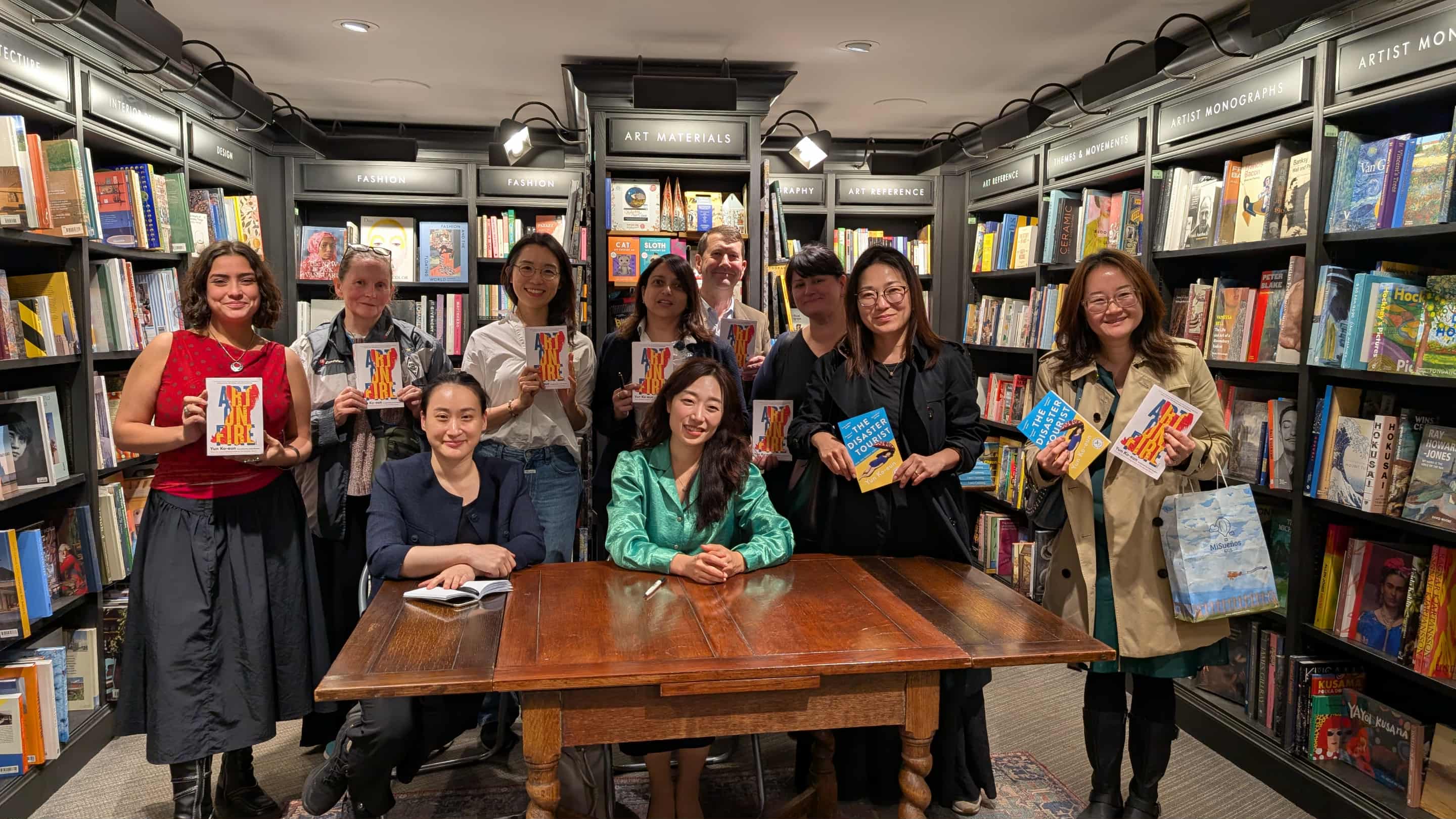

In the autumn, at Wimbledon BookFest, I met readers encountering Korean literature for the first time — some drawn by a particular author, others by a single translated title that opened onto many more. One woman, attending her first literary event, spoke about discovering Korean fiction through A Magical Girl Retires by Seolyeon Park, translated by Anton Hur, and wanting to read beyond the few names she already knew.

Around the same time, I listened to Anton Hur speak about translation with real intensity. Using Han Kang’s Nobel Prize as a point of reflection, he spoke about the responsibility and persistence translation demands — situating Korean literature within wider questions of prize culture and the Anglophone literary world. What stayed with me was his conviction: a sense of translation as care, commitment, and belief in the work itself.

At another Wimbledon BookFest event, a brief exchange with a Korean reader living in London — there to hear Bora Chung speak — reminded me of the multiple routes through which Korean literature travels: between languages, between countries, and between readers with different relationships to the original text.

Closer to home, conversations with colleagues echoed similar patterns. One colleague described discovering Korean literature through Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop by Hwang Bo-reum, translated by Shanna Tan, a novel often grouped within what is now described as K-healing literature. Alongside other titles published in the UK this year, it reflects a growing interest in quieter forms of reading — stories that favour everyday settings, slower pacing, and moments of pause shaped by reflection.

This year, I was also struck by Korea’s outdoor reading events, which encouraged people to engage with literature collectively. Reading is often understood as a solitary activity, unfolding at an individual pace and in private time. Yet these events suggested another possibility: reading as shared presence. Group activities can form around the act of reading itself — book clubs, public readings, or even moments of silent reading together — where connection is felt without the need for conversation.

As the year draws to a close, these encounters suggest that Korean literature’s growing presence abroad is not tied to a single prize or season, but to an ongoing conversation sustained through translation, shared reading, and quiet exchanges between readers. Looking ahead, I’m eager to meet new readers, and to encounter undiscovered Korean authors — alongside the translators and writers who continue to bring this literature into view.

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0