[INTERVIEW] Hyungwon Kang: Preserving Korea’s History Through Photojournalism and Seonbi Thought

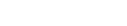

2025-12-19In the field of visual journalism, few photographers have documented global history and cultural identity as extensively and rigorously as Hyungwon Kang (강형원). Syndicated columnist, Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, and visual editor, Kang has spent almost forty years as a witness to the world events of the day and employed photography as a universal language to tell the truth across borders. His work encompasses frontline reporting on U.S. politics, international crises and Korean history; a lifelong interest in telling stories using facts through images.

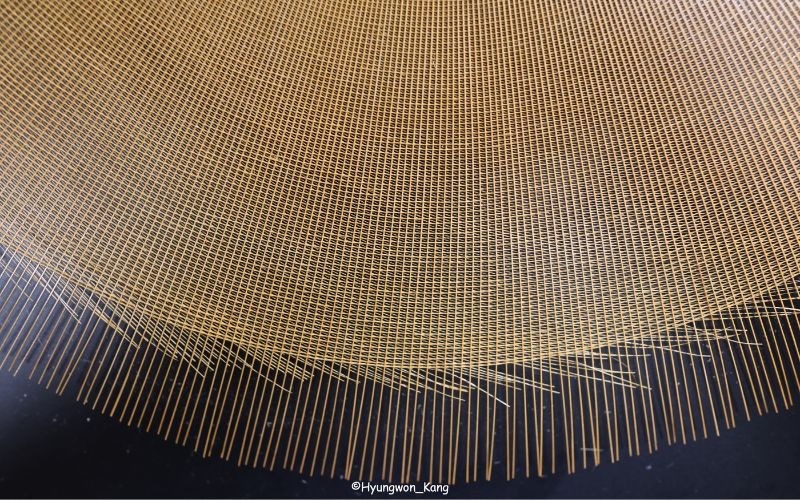

The professionalism of journalism and historical investigation is combined by Kang into a unique visual story that makes him one of the most powerful Korean photojournalists in the English-language media market. His Pulitzer Prize-winning career covered the Los Angeles Riots, the impeachment of U.S. President Bill Clinton, North Korea, and the Olympic Games, and he is the first and the first to win the Pulitzer Prize twice. More recently, he has shifted his interest to writing about Korean civilization and cultural heritage to the attention of foreign readers; the most prominent of these works is his book Visual History of Korea, but also his latest offering, Seonbi Country Korea: Seeking Sagehood, which appears at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2025. His work demonstrates an increasing global fascination with Korean history, moral philosophy and visual history outside of popular culture.

After his recent release of Seonbi Country Korea: Seeking Sagehood and his previous book, Visual History of Korea, I was able to interview Kang via email on his photojournalistic work, the values which inform his visual narratives, and his thoughts regarding offering Korean heritage to the world.

Below are excerpts from the email interview conducted between June 9 and December 15 , 2025.

● What made you believe photography could be a powerful way to tell Korea's story to the world?

Photojournalism is among the most powerful forms of communication. Through visual storytelling, it transcends language and cultural barriers, reaching audiences across cultures with immediacy and clarity. As a photojournalist, my strength lies in this visual language. I use photography to document Korean civilization, history, and culture, presenting them through a universal medium that can be understood and appreciated by people everywhere.

● Your career spans decades of world events, yet you’ve chosen to focus deeply on Korean culture. What compelled you to turn your lens toward Korean heritage and identity?

As a Korean American who has worked in U.S. mainstream media for more than three decades, I recognized a significant gap in accessible, English-language resources on Korean history and culture. To promote a more balanced understanding of world history, I saw the need to present Korean civilization, history, and perspectives through Western storytelling formats, in English, for journalists and the broader English-speaking audience.

● In creating the Visual History of Korea, how did you balance artistic storytelling with historical documentation?

American photojournalism is rooted in fact-based storytelling. While it relies on rigorous journalistic observation and historical accuracy, it also incorporates artistic elements to engage viewers visually and emotionally. This balance allows photojournalism to document history with integrity while presenting narratives that are compelling, impactful, and memorable.

● You’ve spent decades abroad, yet remain deeply rooted in Korean culture. How has this dual perspective shaped your visual storytelling?

Over nearly half a century as a Korean American, my identity has evolved without losing its core, even as Korean culture itself has continued to change. Through my visual storytelling and written work, I am trying to help global audiences gain a deeper understanding of Korea by placing its history and culture within the broader context of English-language historical narratives.

● What aspects of Korean heritage do you think remain underrepresented or misunderstood internationally?

Several critical aspects of Korean heritage remain underrepresented or misunderstood internationally, particularly ancient Korea’s early technological innovation, military sophistication, and historical resilience.

First, Korea was among the earliest civilizations to employ a maritime compass, known as Lachimban—derived from La of the Silla Kingdom—to navigate open seas without visible landmarks, even when stars were obscured. This practice was documented by the Japanese monk Ennin (794–864) and reflects an advanced understanding of navigation that is rarely acknowledged in global histories of science and exploration.

Second, ancient Korean cavalry adopted the use of stirrups centuries before their widespread adoption in Europe. This innovation greatly enhanced mounted warfare and contributed to Korea’s military effectiveness, yet it is frequently overlooked in comparative military histories.

Third, despite repeated invasions, Korean civilization was rarely fully conquered by external forces. A decisive turning point occurred only after the Donghak Peasant Revolution (1894–1895), when grassroots reform movements were brutally suppressed by the Japanese military using modern weaponry. This defeat weakened Korea’s sovereignty and ultimately enabled Japan’s colonial annexation of Korea in 1910.

Finally, Korea’s naval strategy under Admiral Yi Sun-sin remains insufficiently recognized. His use of the Hakikjin, or Crane Wing Formation, was instrumental in defeating Japanese naval forces during the Imjin War of 1592. Ironically, this same formation—derived from Yi’s tactics—was later employed by the Japanese navy to defeat the Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905.

Taken together, these examples reveal a legacy of innovation, strategic brilliance, and resilience that merits far greater recognition in global historical narratives.

● As Korea becomes globally known through K-pop and dramas, what deeper cultural values do you wish global audiences could see?

As Korea gains global visibility through K-pop and television dramas, I hope international audiences will come to appreciate the deeper cultural values that underpin Korean identity. Korean culture extends far beyond popular entertainment and is rooted in one of the oldest continuous civilizations in East Asia.

Throughout history, Korea has remained at the forefront of innovation—from early mastery of sophisticated bronze technology to advanced steel production for weapons and armor. Korea also led one of history’s earliest printing revolutions through woodblock printing, emerging at least five centuries before the printing revolution in Europe.

Equally significant is Korea’s intellectual tradition, shaped by the use of two writing systems: Hanja, which functioned as a shared written script across East Asia, and Hunminjeongeum, a uniquely scientific and inclusive alphabet designed to promote universal literacy and capable of transcribing all sounds. Together, these achievements reflect enduring Korean values of ingenuity, knowledge-sharing, and cultural depth—foundations that continue to inform contemporary Korean creativity and its growing global influence.

● In your experience, what is Korea’s most visually powerful cultural symbol, and why?

The Korean writing system which King Sejong the Great invented. The Hunminjeongeum truly is the most accurate way to transcribe. Any sounds in the universe. It is the solution to be the most accurate writing system for most of the world's 7,000 languages.

● As the first Korean to win the Pulitzer Prize twice, how has that recognition influenced your sense of responsibility in sharing Korean stories?

As the first Korean to win the Pulitzer Prize, and first to win the second Pulitzer, the recognition has deepened my sense of responsibility to chronicle Korean stories for the rest of the world. Outside the Korean-language ecosystem, much of the global intellectual community knows remarkably little about Korean history and culture—despite Korean ancestors’ role as one of East Asia’s oldest civilizations.

In that context, I chose to focus my work full time on documenting and narrating Korean history and culture through the lens of a 21st-century American journalist. My goal is not only to inform contemporary audiences, but also to ensure that accurate, fact-based Korean narratives become part of the global knowledge record—including the emerging knowledge bases that inform large language models and future AI systems. In doing so, I hope my work will serve as a reliable foundation through which future generations can better understand Korea’s history, culture, and contributions to world civilization.

● In an era where AI can generate images and narratives, what remains uniquely human about photojournalism?

The most valuable images are original images—those created through direct human presence and lived experience. Photojournalism is the art of visual storytelling grounded in original observation, where the photographer bears witness to real events in real time.

While AI can efficiently organize vast amounts of information and generate convincing visual narratives, AI-generated images lack the authenticity and accountability that define photojournalism. They do not carry the human judgment, ethical responsibility, or personal imprint—the “fingerprints”—of a photojournalist who was physically present at the moment of history.

True Photojournalism work can withstand the test of time and become a historically authentic and factual record for eternity.

● Your new book, Seonbi Country Korea: Seeking Sagehood, was introduced at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2025. What drew you to the Seonbi tradition at this stage of your career?

Korean history and culture are best understood through the long evolution of Korean civilization over millennia. At its core, this civilization has been shaped by the institutionalized formation and sustained practice of Seonbi virtues. These ideals—emphasizing moral integrity, intellectual rigor, and social responsibility—have served as a foundational framework for Korean society. Even today, Korean leaders are evaluated not only by their intellectual abilities, but also by how closely they embody the ethical standards and character associated with the Seonbi character tradition.

● The Seonbi spirit centres on integrity, humility, and scholarship. How did you translate these intangible values into visual storytelling for the book?

In my book Seonbi Country Korea, Seeking Sagehood, I defined the Korean Seonbi value system into five character words: discipline, courage, inclusion, wisdom, and honor. In my storytelling pictures, I show and define Korean history and culture according to those five value vocabularies.

● What do you hope international readers understand about Korean identity through the lens of Seonbi sagehood?

Korea is the only country in the world where for a large percentage of intellectual elites, pursuit of becoming a sage was an academic and philosophical goal. Material wealth or government appointments were irrelevant to the spiritual perfection of a Seonbi individual whose goal in life was seeking to be a better person, and to create a better world for everybody to live in.

● As someone who mentors and lectures widely, what guidance would you offer young creatives passionate about documenting Korean culture?

There are distinctively Korean visual elements in Korean culture and history. For example Hanok buildings have elements such as a ventilation door under the ceiling above the door frame which was a natural way to ventilate the room. It was the original HVAC system which does not require any electricity. Such details define Korean innovation and scientifically minded housing design.

As a writer of history, as it happens, and a scholar of the philosophical heritage of Korean civilization, Hyungwon Kang stands on the boundaries of journalism, cultural memory and moral duty. By telling the stories through visual facts, he places Korean history not as a peripheral story, but as a central component of global civilization, which can be characterised by innovation, resilience, and moral question. Visual History of Korea and Seonbi Country Korea: Seeking Sagehood, are examples of his life-long effort to leave the world with an authentic, lasting record of Korea. At a time when the world is characterized by the rapid change in technology and unnatural narratives, the photography of Kang confirms the permanence of the human presence, original observation, and cultural truth, that the past, values, and intellectual legacy of Korea are still visible, verifiable, and remembered.

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0