Netflix Korea’s first original animated feature film, “Lost in Starlight”, premiered on May 30, 2025, and has since earned a place on the eligibility list for the Animated Feature Film category for the 98th Academy Awards. This achievement marks not only a personal milestone for its creators, but also a historic moment for Korean animation on the global stage. Alongside a small number of Korea-affiliated international features, including “KPop Demon Hunters,” “Lost in Starlight” stands out as the only fully Korea-produced film among the eligible entries, collectively helping introduce Korean creative voices and cultural influences to far broader international audiences.

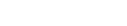

In our interview, the film’s creator and director Han Ji-won shares how her childhood love of animation grew into a career and ultimately into “Lost in Starlight.” She speaks for the first time with Korea.net about the film being recognized on the Academy Awards eligibility list, reflecting on what this milestone means not only for her personally but for the visibility of Korean animation worldwide. Leading Netflix Korea’s first original animated feature, Han sees this moment as the beginning of a broader shift in how Korean animated storytelling is valued on the global stage.

This interview was conducted in written form via email between November 3 and December 15.

Did your love for animation start early in life?

Yes. Even before kindergarten, my twin sister and I were constantly drawing, and throughout school I spent every break and every after-school moment making comics, even joining a comic club in middle and high school. My grandmother ran a comic book rental shop, so I grew up surrounded by manga I loved. I originally wanted to attend a specialized animation high school, but at my parents’ suggestion I entered an arts high school instead. Later, I went through Korea’s intense art entrance exam system again in order to get into the Animation Department at the Korea National University of Arts, finally studying the major I had always dreamed of. From my first year there, I began creating animations, and I have continued ever since.

Growing up in Korea in the 90s and early 2000s, what was it like discovering animation?

Animation was the main content children consumed in Korea, just like in many other countries. When I was young, Korea was going through a period of opening up to Japanese culture. Before that, Japanese content could not be officially imported, but once the law changed, we suddenly had access to an entirely new world of animation. That was when I first encountered “Princess Mononoke” and realized that many of the works I had loved were actually Japanese. It opened my eyes to auteur-driven animation and made me feel that this medium could express something much deeper.

In the 1990s, some 2D animations aired on Korean TV, but by the early 2000s there were even big-budget titles aimed at adults, although commercial failures stalled future investments. Back then, Korean children and teenagers could still watch Korean 2D works on TV, a situation that has now almost completely disappeared, which I find unfortunate. Those regrets made me want to create works like the Japanese animations I admired but rooted in Korean contexts and stories. Korea and Japan share similarities such as school uniforms, intense entrance exams, social politeness, and hiding one’s true feelings, yet there are striking cultural differences as well. That mix of familiarity and distance inspired me creatively, while the frustration pushed me to develop my own artistic voice.

How did the idea for “Lost in Starlight” first take shape?

Most people have big dreams, but not everyone gets to pursue them. My first film, “Kopi Luwak”, was about high school friends who give up on their dream of becoming rock stars; this was because dreams had always been a central theme for me. Growing up in Korea’s competitive art education system, I saw classmates forced to quit because their families could not afford lessons, while others reluctantly pursued art because their wealthier parents believed it would lead to a good university. It was my first glimpse of social unfairness, and it made me question why I was so obsessed with dreams. As I got older, I saw many women around me giving up their dreams not just because achieving them was hard, but also because of gendered expectations and responsibilities imposed by society. My mother’s generation especially had to sacrifice their first dreams for marriage and family; my own mother once dreamed of becoming a voice actress. She has since found second and third dreams, but that early loss still left a deep impression on me.

Space has always fascinated me, partly because so many works which I loved, such as “Cowboy Bebop” and “Ulysses 31”, were set in space. Astronauts feel like the clearest metaphor for dreams: many aspire, only a few reach that height, and some even risk their lives trying. In my past films, I often equated dreams with death or curses; in “Kopi Luwak”, one of the characters dies while chasing his dream. We often hear of manga artists and animators who pass away from overwork, or athletes who die pursuing passion. Dreams shine from afar like stars, but the path toward them can be long, dangerous, and sometimes fatal. From that perspective, making the protagonist of “Lost in Starlight” an astronaut felt natural, because their profession embodies both the brilliance and the cost of chasing a dream.

How did the partnership with Netflix Korea come about?

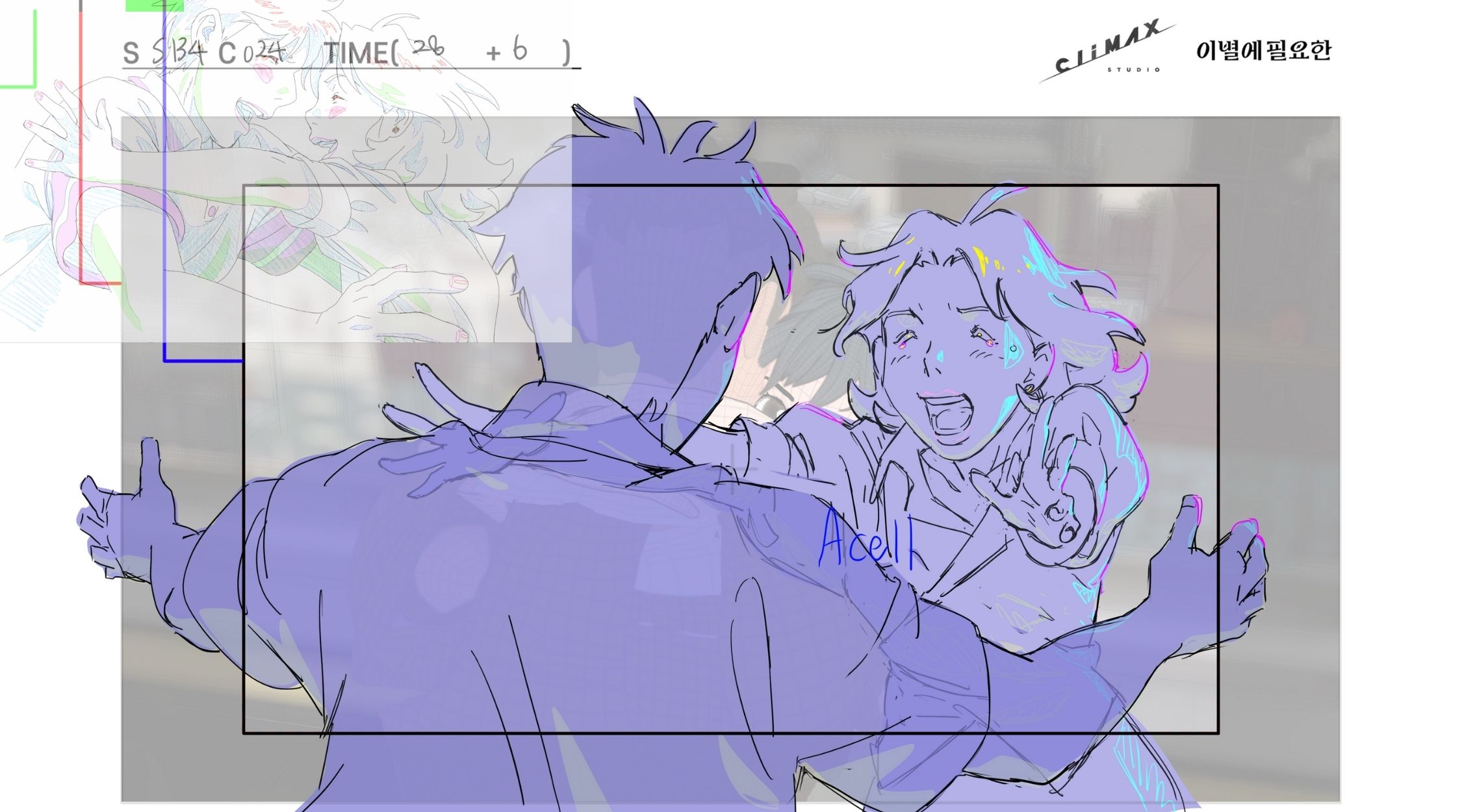

“Lost in Starlight” was developed together with Climax Studio, which had already worked extensively with Netflix on projects such as “Hellbound” and “D.P”. Since our film was not aimed solely at children or teenagers, unlike many theatrical animations, Netflix’s audience and reach made it a natural fit. At the time, Netflix Korea was not strongly focused on producing animation, but many of its producers were passionate animation fans. Before our pitch, several even told me they already knew my work and were fans, and that enthusiasm played a meaningful role in bringing this partnership to life.

What can animation do that live-action cannot?

In animation, nothing appears on screen without intention. Even a speck of dust must be drawn consciously. Live action also requires careful planning, but animation demands imagining everything: the protagonist’s senses, emotions, the air, the humidity, even scents, in order to create a believable atmosphere. That process makes me embody the protagonist more deeply and connect to them with greater intensity. To express emotions convincingly, I have to constantly answer inner questions, sometimes ones I might otherwise avoid, which feels almost like psychological counselling. Because of this, animation allows me to uncover and communicate hidden emotions in ways that live action cannot.

How did you assemble your creative team, especially emerging talents? I previously had the opportunity to interview Yoon Je An, who worked on this project as the Sakuga Director, and I’m curious about your approach.

Yoon Je An was the first artist I personally contacted for the film. He is my junior from university, and I already knew his strengths from earlier collaborations. He had directed his own student works, and on this project he served as the character designer and head model check artist — a role known in Japanese 2D animation production as a Sakuga Director. I was confident that no one could do it better. He not only understood my visual style and design sensibility, but also brought a strong foundation in anatomy, which is rare. I trusted my instinct over his résumé, because for me, communication and shared taste are far more important than career history. Aesthetic sense is difficult to teach, so when it aligns naturally, collaboration becomes much smoother. As a result, our team was very young, with an average age in the late twenties, and we maintained a friendly and casual atmosphere. Many of the key artists who worked closely with me earned their very first professional credits on this project.

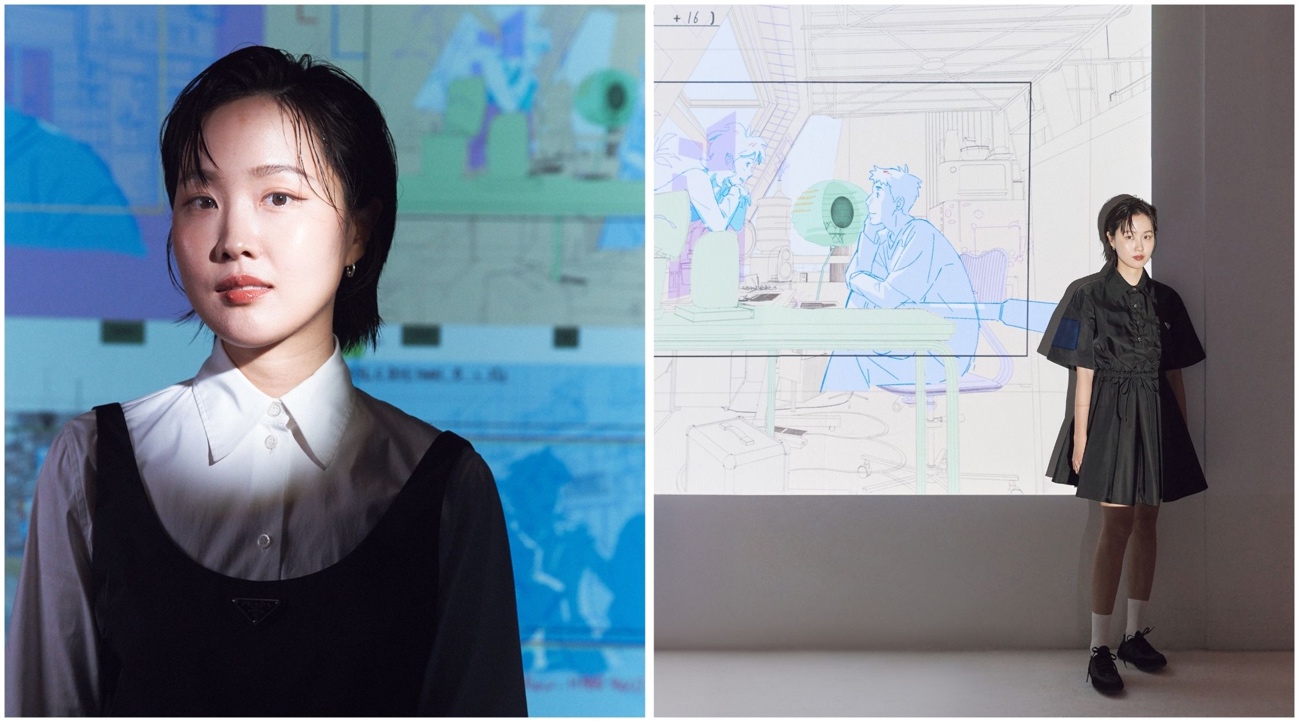

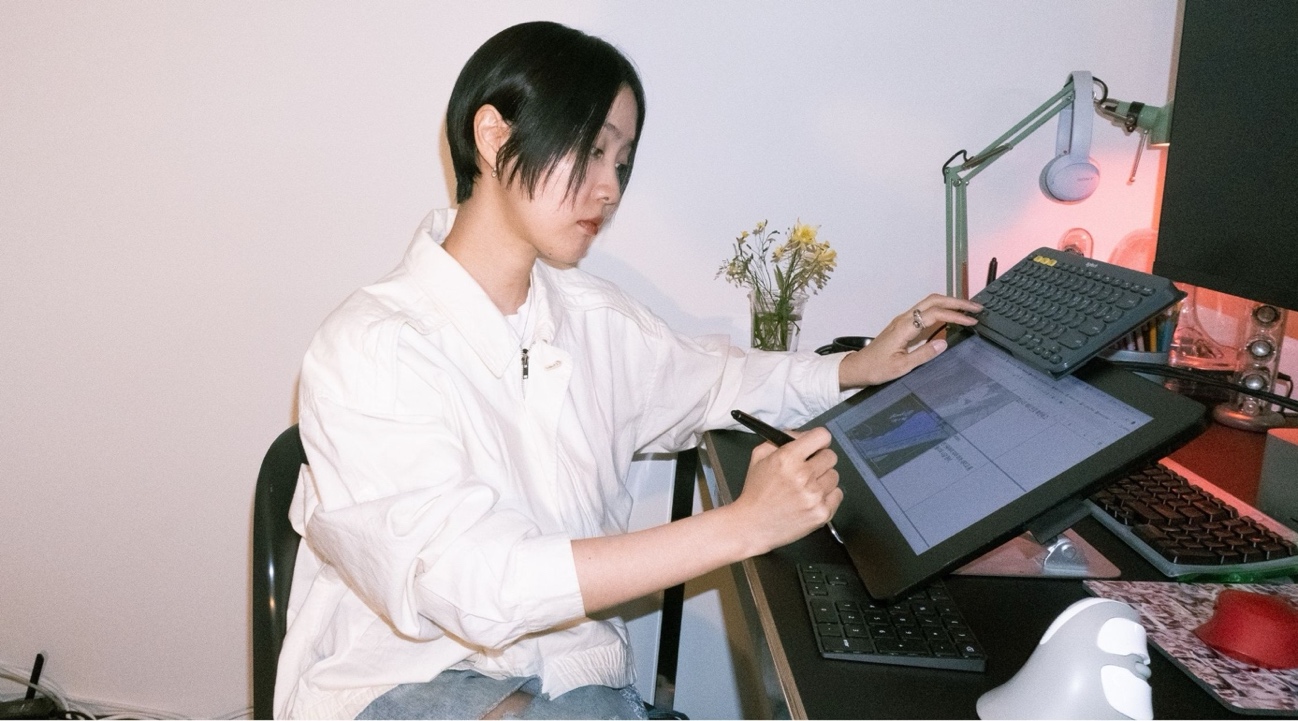

What was the production process like?

I am still processing the difficult, joyful, and overwhelming memories from that time. It was incredibly challenging but deeply rewarding. We completed an animatic once, but kept revising it far into production, long after we should have stopped. We even made script changes after deadlines had passed. That pushed the production schedule to an unbearable level, and I had to ask the team for patience, which was emotionally very hard. Still, if we had not made those late changes, I would have regretted it, because many of the audience’s favourite scenes came from that period.

From pre-production to completion, the film took about 2 years and 3 months. Considering that many of us were working together for the first time, it was an extremely short timeline. Even finishing the animatic within six months was daunting. Honestly, every step felt like facing the question “is this even possible?” and each time the answer seemed to be “yes, and it can get even harder.” In the final three months, I barely slept. It felt like a war. I do not take pride only in that struggle; I also feel deeply grateful to the artists I care about. Yet in the midst of all that, I also remember laughing together and finding small moments of happiness. The team even created fun groups like a bread club or a running club that met outside of work, and they always invited me. The project holds both some of my most exhausting memories and some of my happiest ones.

What was it like to take on both writing and directing in such a large-scale production?

Independent animation and commercial animation are almost opposite in production style. In independent work, I make decisions entirely on my own, with no need for approval or persuasion, and communication with a small team is much simpler. In commercial work, that balance flips completely. I had to explain, persuade, and build understanding at every step, and my main responsibility shifted from drawing to talking and writing. Still, the core remained the same: Protecting emotional truth. In independent projects, I asked myself the questions; here, others asked me, and I answered.

Keeping my core ideas alive was essential. Independent filmmaking taught me to keep questioning myself, and that practice helped me here as well. Yet seeing a shot pass through many hands brought mixed emotions. Sometimes it improved beautifully, and other times the original intention became diluted, or mistakes multiplied. That is the paradox of animation: the creator’s identity always appears, whether it is concentrated in one person in indie work or shared among many in commercial work. Because I conceived this project from the script stage, I had clear answers about most directions, but when I did not, I discovered them through conversations with the key artists. It opened me up more as a director, teaching me to listen and to trust. During planning I tried to stay open and collaborative; during production I worked to give sharper and more decisive feedback.

How did you capture emotional intimacy within a futuristic sci-fi setting?

When dealing with futuristic elements, I did not want them to look like spaceships or machines. I wanted them to feel like familiar objects such as buildings or furniture. Many sci-fi films design Earth to resemble a spaceship, but unless the atmosphere suddenly disappears, there is no reason everyday items would evolve that way. That approach felt conventional rather than practical or fresh. Since our story is set 25 years in the future, I looked back at Korea 25 years ago and imagined how it might naturally continue developing. Because trends in music and fashion cycle every 20 to 25 years, I envisioned a future infused with nostalgia.

When people travel alone, even when seeking something new, they inevitably carry inner questions and hope to return with answers. I believe what humans truly seek in the future is not an escape into the unfamiliar, but a deeper return to themselves. In films like “Her”, technology leads us back to our own humanity, and I wanted to show a similar truth. Even in the future, what we long for remains profoundly human.

What are your thoughts on “Lost in Starlight” being listed as Oscar eligible, and what kind of impact do you think this could have on the future of Korean animation?

This year has been an exceptional one for Korean feature animation, with many strong works being released. Being listed as Oscar-eligible among them is truly an honour. As far as I know, it’s quite rare for a Korean animated feature to make it onto this list, so I’m genuinely grateful for the recognition. I’m not holding any grand expectations, especially with so many remarkable contenders from around the world this year. I’m simply happy to see our film listed alongside works I personally admire.

Beyond this listing, several outstanding Korean animated features have been screened at major international festivals throughout the year. I believe this demonstrates that Korean animation is now being recognized at a global standard. I hope this momentum leads to opportunities for attracting international investment and fostering collaborative partnerships, enabling Korean animation to continue growing not only domestically but on a much larger global stage.

If you could send a message to 2050, what would it say?

I hope my work will still hold value as a reference for them. Time will change many things, but I believe “love” will still mean the same. Love wins all.

What hopes do you have for the future of Korean animation?

I am still cautious about judging my own achievements. As I mentioned earlier, I am still digesting the many emotions from this project, and I want to slow down a bit, keep working at my own rhythm, and focus on themes I truly care about. During production, people would often joke, sometimes quite seriously, that the future of Korean animation depended on this film’s success. That was a heavy responsibility, and I worked very hard with that in mind. Whether I lived up to it will become clear with time, and I am not ready to evaluate it yet. What I do believe is that Korean creators have already shown remarkable storytelling, technical skill, and aesthetic sensibility. Since animation is a medium that requires all three, its potential in Korea is enormous, as long as the right support and environment continue to grow.

What projects are you interested in next? And are you working on anything with your sister?

Yes, we are preparing projects together. Right now, I’m developing both a feature and a short, and they both draw heavily from the artistic inspiration of my twin sister, Ram Han. Her artwork has a very unique, organic feeling, and we’re shaping genre stories that make the most of that aesthetic. Both are fantasy-leaning sci-fi projects, so they’ll have a different flavour from “Lost in Starlight”. I’m very excited to share them when the time comes.

How about this article?

- Like3

- Support0

- Amazing4

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0