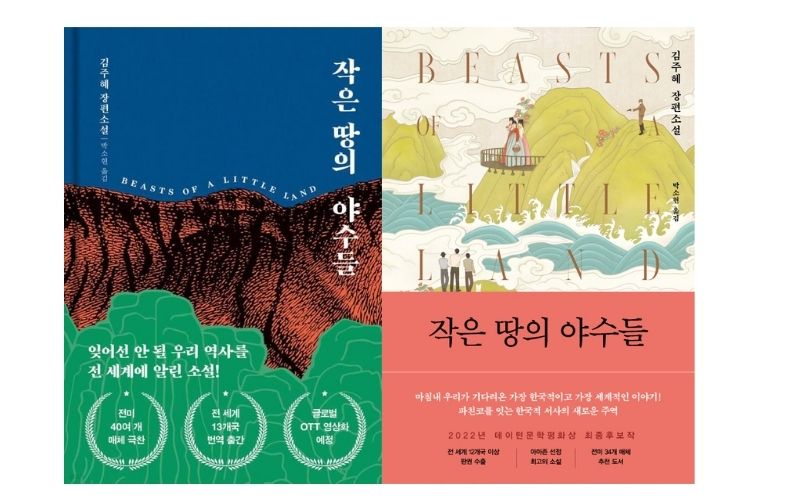

Juhea Kim is an internationally acclaimed author whose works explore history, art, and humanity with a deeply personal and morally engaged voice. Her debut novel, Beasts of a Little Land, tells an epic story of love, war, and redemption set against Korea’s independence movement.

Beginning with a tiger in the snowy mountains of 1917, it follows Jade and JungHo through survival, friendship, and revolutionary struggles over half a century. A portion of the book’s royalties benefits the Phoenix Fund, a nonprofit for Siberian tiger and Amur leopard conservation.

Her second novel, City of Night Birds (a Reese’s Book Club pick), follows Natalia Leonova, a ballerina returning to St. Petersburg after a career-stalling accident. Confronted by love, betrayal, and her past, she must decide whether to reclaim her stage or walk away forever. The novel explores love, forgiveness, and the making of an artist in a turbulent world.

Beasts of a Little Land was a finalist for the 2022 Dayton Literary Peace Prize, won the 2024 Yasnaya Polyana Award, and earned multiple other international recognitions. Both novels have been widely translated and critically acclaimed.

Her upcoming short story collection, A Love Story from the End of the World, explores humanity’s relationship with nature across different eras and settings, representing a natural progression of her work.

In this exclusive interview, we discuss Juhea Kim’s Korean heritage, acclaimed awards, creative process, and the inspirations behind her novels and short stories, highlighting her remarkable ability to blend historical, cultural, and ethical perspectives into immersive literary experiences.

The following are excerpts from an interview conducted via email on 1 October 2025.

Could you please introduce yourself briefly?

I’m Juhea Kim, the author of Beasts of a Little Land, City of Night Birds, and upcoming A Love Story from the End of the World. I have been living in London for the past two years.

You were born in Korea and raised abroad. How have your Korean heritage and the country’s history and culture shaped your identity as a writer and as a person?

First, language shapes values, and values shape writing. Korean has deeply informed who I am as a person and an artist. I write in English, which allows for long sentences, paragraphs, and novels, supporting expansive thought. But Korean is particularly attentive to relationships, with numerous conjugations reflecting age, gender, and social roles, encouraging empathy—a quality essential for any writer.

Second, I was shaped by the Korean concept of the artist-intellectual—문인—a person of letters who is not only a writer, but also a painter, poet, philosopher, and social leader, responsible for proposing moral direction even at personal sacrifice. This sense of responsibility for both art and the world is central to my identity as a writer.

You were a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and the winner of the Yasnaya Polyana Award. What do these recognitions mean to you as a Korean author writing for a global audience?

A writer must never write with the goal of winning awards or selling a lot of books. While I’m creating, my intentions must be absolutely pure. But after it’s turned into a book, I do hope to reach an audience and receive critical attention—because after all, an extraordinary amount of effort and life force goes into that book.

That’s why I’m deeply moved and humbled to have received these recognitions. Interestingly, they both emphasize literature’s role in promoting peace, which of course made them even more meaningful to me. I wrote a novel of Korean history from a Korean point of view, aesthetically and morally. So, it was incredibly affirming to be accepted and celebrated in two such distinct literary cultures, the US and Russia.

Beasts of a Little Land and City of Night Birds both received great recognition. Could you share what inspired these stories?

Almost everything I write originates from a moment of inspiration, and these novels came to me within a day at most, almost whole. It feels like an illness; it’s also like the moment before you sneeze.

I remember Beasts of a Little Land began on a winter’s day right after a run in the park. I was taking a walk in the springtime when I drew out the majority of City of Night Birds. These are mysterious and sacred moments you can’t explain by logic.

City of Night Birds was also inspired by Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 and by your passion for ballet. Could you tell us more about how music and dance influenced the creation of this story?

When I experience a transcendent work of art, I become possessed by the idea of doing something like that in a literary form. To me, Piano Concerto no. 23 in A major was Mozart’s testament to sacred and profane love—how love in all its shades can be both sublime and degrading. It instantly gave me the emotional tonality of the novel.

And then I knew the structure of the novel had to follow the structure of a concerto, its virtuosity, expansiveness, even caprice. While writing this novel, I danced an hour and a half to two hours a day, most days a week. When I wasn’t dancing, I was watching ballet on video or live, listening to music, or reading about ballet. Everything I was doing physically, mentally, spiritually for the book merged into one creative act.

Since the publication of City of Night Birds, what recognition or event has been the most memorable or meaningful to you?

When a book is first published, you feel like it needs your energy and protection 24/7. Then later, there is a moment when you realize it has a life of its own. City of Night Birds was about three months out when I experienced this. A board member of San Francisco Ballet had read the book, due to a chain of recommendations from professional dancers.

She absolutely loved the book and invited me to speak at SF Ballet. Afterwards, I attended their performance followed by the annual spring gala, where I met so many members of their dance community who raved about my book. I was wearing a beautiful gown and the whole evening felt like a page out of City of Night Birds. This made me realize that my novel could fly on its own now.

Your new short story collection A Love Story from the End of the World is coming out in November 2025. Could you tell us about the inspiration behind this work, and what readers can expect?

My books may seem very different, but they represent a natural progression of who I am. Beasts of a Little Land explored my heritage; City of Night Birds, my love of art; and now, A Love Story from the End of the World focuses on my greatest passion: nature. The collection comprises ten stories set across different eras and places, each inspired by a color—yellow, black, green, white—and envisioned as an exhibition, so that together they form a cohesive artistic statement.

Short story collections often receive less commercial attention than novels, and I am known for classical novels evocative of 19th-century realism, so this collection may fly under the radar. Yet, as a writer, I believe it contains some of my finest work. These stories have made me laugh and cry, and one in particular, set on an Indian Reservation in Oregon, chills me every time I reach its final pages. Above all, I aim to write with soul and urgency, so that readers can feel the passion behind every story.

Your books are being published in many countries, including Russia this year. How do you feel about your stories reaching such a wide, global audience?

The Russian edition of City of Night Birds is due to arrive in October, which is right near the time Beasts of a Little Land is coming out in Romania and Turkey; which is also close to the US/UK publication of A Love Story from the End of the World! It’s very exciting and a bit overwhelming to have publications around the world.

But of course, mostly it’s an incredible honor. Gratitude isn’t a word that’s deep enough to express what I feel for my readers. I’ve heard from people in all continents, so many backgrounds, age, ethnicity…and to see how my books have touched their lives is the greatest gift. Even now, every warm message or meeting with a fan is so uplifting and humbling. I hope they know what a difference they make to my life.

What is your writing process like? Do you have any rituals or habits when you write?

Recently I wrote the first draft of a conservation piece at the airport in Antala, Turkey. This was in the middle of a 45-hour door-to-door journey from Vladivostok to London; I was really exhausted but I had a deadline for a UK outlet.

So, I can write anywhere and anytime, and my first novel especially was written under a lot of duress. But when I can afford to have a calm routine, it makes writing so much more enjoyable. My favorite place to write is my sofa or my bed, in pajamas, with my cats somewhere nearby. That’s it—that’s the routine.

Which authors or works have influenced you the most?

I’ve made no secret of the fact that I’ve been most influenced by the life and works of Leo Tolstoy. I’ve also been very influenced by Kafka, Maupassant, Bulgakov, and Korean authors Choi In-ho (a Catholic writer like me, his faith and compassion glimmer through his prose) and Park Wan-suh (whose 1977 novel <휘청거리는 오후> taught me how to write a multiple 3rd person POV).

Your work often reflects a deep sense of compassion and connection to the world. How do your values shape your writing, and what do you hope readers take away from your stories?

I appreciate you saying that about compassion and connection in my work. That makes me feel like my efforts are not futile. People commonly discuss literature in two ways: form and substance. The ideal is for the form and substance to be wholly unified, and for that unity to be truthful and beautiful.

But if I had to give precedence to one, I would say substance—the message—should come first. This message has to come from the soul and the conscience of the author and speak to the soul and the conscience of the reader. Mine has always been that compassion gives meaning to our existence, and if the readers can hear that message from my soul, then my stories have fulfilled their purpose.

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers, especially those with multicultural or diaspora backgrounds?

One of the questions I get asked most often is, “How did you do research for your books?” I used to wonder why, until I realized what people are really asking is, “If I do great research, could I write a novel?” The truth is, anyone can research online, but research is not the hardest or most important part of writing. I advise writers to observe the world instead.

I sometimes see people who have no interest in trees, flowers, or small creatures claim they are writing a novel—and that is not a good place to start. Turn off your phone, notice the bees, birds, even snails, and see the world from their perspective.

This is where empathy begins, and where the ego must soften to become an artist of the world. Avoid writing solely for yourself, and in all personal and professional matters, be kind, decent, reliable, and hardworking. For writers from multicultural or diaspora backgrounds, the very differences that set you apart are your greatest strength.

How about this article?

- Like3

- Support1

- Amazing11

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful1