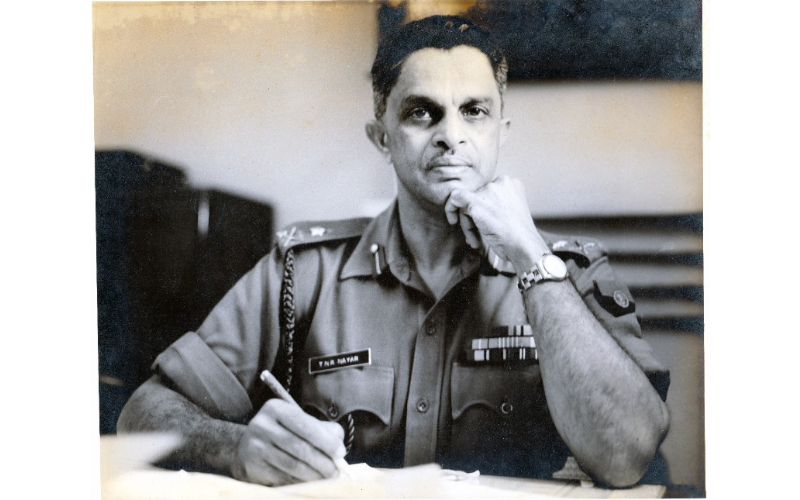

"Limits of Change," an immersive art and theater experience presented by InKo, delves into a largely obscured chapter of Indo-Korean history, utilizing the personal archives of General TNR Nayar, an Indian soldier deployed to post-1953 Korea, as a foundational narrative. This exhibition, scheduled for the Lalit Kala Academy from February 8-20, 2025, is conceptualized and executed by his daughter, multidisciplinary artist Parvathi Nayar, and masterfully blends historical documentation with fictional elements to explore profound themes of identity, and reconciliation.

Through installations, videos, and archival materials within a fictional "Story Museum," the audience is guided through the experiences of Indian soldiers and displaced POWs, highlighting the cultural and emotional complexities of their role in post-war Korea and fostering intercultural dialogue.The project emphasizes the CFI's role in post-war Korea, It aims to foster intercultural dialogue and reveal the enduring historical ties between India and Korea.

Parvathi Nayar is a Chennai-based multidisciplinary artist and writer whose practice critically engages with sustainability, climate change, and ecological concerns, notably through the recurring motif of water. Working across drawing, installations, mixed media, and video, Nayar's artistic output demonstrates a profound commitment to environmental awareness.

As a founder-member of The #Collective, Parvathi Nayar fosters collaborative projects at the intersection of art, environment, and socio-cultural issues.

Through an email interview conducted between February 20 to March 8, Parvathi Nayar shared her insights into the significance of the exhibition and her perspectives on the evolving Indo-Korean relationship. She articulated the importance of revisiting her father’s experiences to illuminate the enduring historical ties between India and Korea, emphasizing the necessity of understanding past interactions to navigate contemporary relationships.

She discussed how her father’s generation contributed to building bridges during a period of immense upheaval, and how contemporary cultural exchange and economic cooperation have further strengthened these ties.

What sparked your initial interest in the Custodian Force India (CFI) and this relatively unknown chapter of Indo-Korean history?

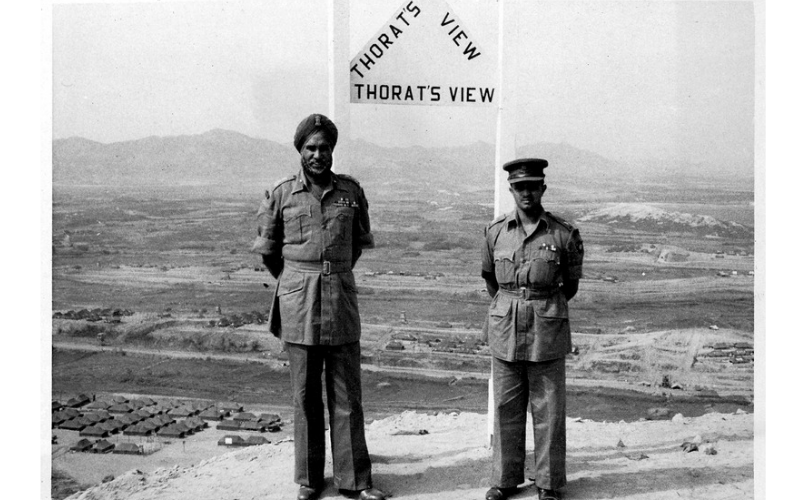

I had long wanted to do a creative project with my father’s personal archives – his papers, photographs and videos – as well as my memories of the kind of person he was – an army General who believed in peace, fairness, the absence of hate and the power of forgiveness.Delving into the material and subsequent research highlighted how the story of the Custodian Force India was a forgotten chapter of history – one that few knew about, yet one of immense significance. When I took the project to Director Dr Rathi Jafer, Director, InKo Centre, Chennai, she was struck by its layered aspects.

This was independent India’s first step onto the global stage, a moment of profound hope and idealism. It marked a time when our nation, newly unshackled, engaged with the world not through conflict but through peacekeeping. The excitement of rediscovering and reinterpreting this overlooked history fuelled my commitment. After all, histories are not just meant to be remembered; they must be reimagined and retold, ensuring their relevance in the present.

Can you elaborate on how your father's experiences as part of the CFI influenced and shaped "Limits of Change"?

My father’s journey to Korea was a part of our family’s history - present, yet in the background, like a faint echo of another time. It was only when I began working on Limits of Change, and particularly the 8mm films my father shot the Custodian Force India in the Korean DMZ in1953-54, that I experienced a kind of time travel - seeing that world through his eyes, framed by his lens. Though a lot of the film had deteriorated by the time I digitized it, what remained still held the power to transport.My mother’s recollections added another dimension - she spoke of the deep anxiety she felt as a young bride, knowing little about this distant, cold land where my father had been sent. And beyond the memories, there were the stories that helped activate the imagination - the adventures he spun for me as a child, featuring the enigmatic Miss P and her companion, Helicopter, a shape-shifting creature. It was only much later, when I learned that it was in Korea that Indian soldiers had their first experience riding helicopters, that I wondered - was this where my father’s fascination with helicopters began? Had Korea, in ways unseen, shaped the stories of my childhood?

Limits of Change emerges from these fragments - archival, remembered and imagined - exploring the shifting boundary between history and storytelling, fact, fiction and the personal mythologies that shape us.

How did your post-pandemic trip to the DMZ impact your understanding of the CFI's role and the stories you wanted to tell?

We felt it was important to visit Korea before finalising the shape of Limits of Change – a research trip organised by InKo Centre, Chennai.

Visiting Korea - standing at the DMZ, walking through Geoje-do and Gimhae, tracing the history embedded in these landscapes - was essential. No amount of research could replace the experience of being there: the nip in the wind, the latent echoes of history, the weight of division. It shaped my understanding of the Custodian Force India’s role in ways that went beyond facts - it became more visceral, embodied.

Our earlier work, Chicken Run, had already explored this entanglement of history and fiction, telling the story of the Koreans who returned to India with the CFI. Presenting it at Hankuk University deepened our engagement, as did our journey through historical sites such as Incheon with Professor Yoondho Ra, whose own fascination with - and research into - this overlooked chapter of Indo-Korean history complemented ours.

This trip gave Limits of Change its texture, its sensory depth. The look, the feel, the scent, the sound of Korea seeped into the work, transforming it from an abstract historical inquiry into something lived and felt. The experience also led to me creating with designer VS SIndhura, a coffee table book titled Messages in a Turtle Box. The book, braided into the fictional world of Limits of Change, is ascribed to one of its characters, Curator P. These layered narratives - archival, imagined, and experienced - blur the boundaries of time, making the past feel very present.

"Limits of Change" blends theatre, art, spoken word, and text. How did you and Nayantara Nayar decide on this multi-disciplinary approach, and what unique perspectives did each medium bring to the story?

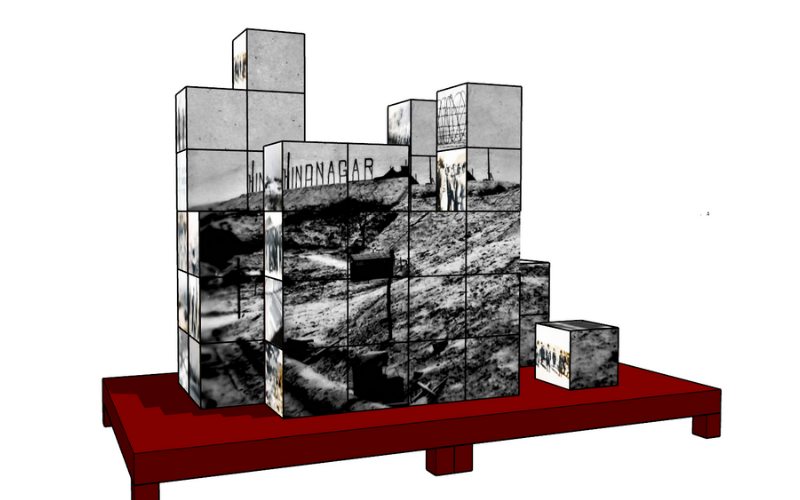

I began work on Limits of Change over six years ago when I invited my niece, Nayantara, a talented playwright, to collaborate with me on this project. From the outset, I had felt that the story – rooted in both personal and historical narratives – demanded a multidisciplinary approach. By interlacing fiction, fact and fable through theatre, art, the spoken word and text, we sought to create a layered and immersive experience within an imagined space we called The Story Museum.

Each medium brought something unique: theatre gave the narrative immediacy, art provided a visual depth, spoken word added lyrical resonance, and infographics anchored the work in historical and personal realities. At its emotional core, the piece is shaped by my father’s experiences and the history of the CFI in Korea in 1953-54. I realised how the past lingers, how personal histories intersect with the larger tides of time, and how art, in all its forms, can hold and express these complexities.

This journey has been enriched by amazing collaborators, each bringing their own artistry to the work - InKo Centre, under the able guidance of its director Dr Rathi Jafer, that took on the commissioning and production of this project; visionary director Yog Japee; a wonderful ensemble of actors; designer VS Sindhura and sensitive cinematographer CP Satyajit, among others.

How did you navigate the balance between historical accuracy and fictionalized storytelling in creating this piece? Why was it important to you to "book-end the piece with history and then let fiction take over"?

Fiction possesses a unique power - to illuminate our deepest truths and breathe life into history. In crafting this piece, we never sought to alter or invent history but rather to use historical fiction as a creative lens, seamlessly blending the real and the imagined. This form allowed me to weave together authentic settings, documented events and the emotional weight of real figures alongside imagined characters and moments.By bookending the piece with history, I feel the narrative was anchored in the undeniable reality of the past - reminding the audience that the brave men of the Custodian Force India did indeed stand guard over 23,000 POWs in Korea who refused to return home after the War. This framing device served as a deliberate signal: what lay between these historical markers was a layered fictional tapestry woven from multiple sources, textured with fact and enriched by the imagination.

What specific human stories within the larger context of the CFI and the Korean War did you want to highlight?

Limits of Change delves into lives caught in the tides of multiple wars, illuminating the weight of the choices we make and the human cost of war beyond the battlefield. In focus are both the non-repat POWs from the Korean War who did not want to go to their home countries, and the soldiers of the Custodian Force India, sent not as conquerors, but as guardians and protectors.

Within this historical backdrop, the story narrows its focus to the deeply personal journeys of a few fictional protagonists: Curator P of The Story Museum in the present, piecing together fragments of the past; Capt. N, a CFI soldier grappling with duty and conscience; and two non-repat POWs, torn between the home they left behind, their past deeds and an uncertain future. Their intersecting narratives lie at the heart of Limits of Change.

Why do you believe it is important to tell this story now, and what kind of dialogue do you hope it will spark about Indo-Korean relations and the history of peacekeeping?

As Limits of Change suggests through a letter written by Capt. N, the cycles of violence and war have echoed through human history. Yet, these cycles are not immutable. While we may feel powerless in the face of recurring conflict, we must resist that feeling - because ending these cycles begins with conscious acts: the choice to release hatred, to embrace forgiveness as a radical practice and to remember history not as a burden, but as a guide.

In today’s world, where power struggles and the spectre of war still loom large, this story is a reminder that peacekeeping is not just about neutrality, but also about courage, conviction and the will to break the cycle. By revisiting the intertwined histories of India and Korea, perhaps, we may spark a more universal dialogue on resilience, reconciliation and the ways in which nations and individuals alike can choose to be agents of peace.

In your research, what did you discover about the overall relationship between India and Korea, particularly during and after the Korean War?

There were wonderful snippets of history that I came across. For example, 60 Para Field Ambulance sent by India - under the leadership of Colonel Dr A. G. Rangaraj - is said to have treated an estimated 2.2 lakh patients during the Korean War. Their incredible dedication and courage earned them the title “Angels in Maroon Berets” or going much further back, the story of an Indian princess who sailed to Gaya and married King Suro, establishing a lineage to which millions of Koreans still trace their roots. A fascinating story, made even more compelling by ongoing research suggesting that she may have hailed from the ancient Kingdom of Ay in South India. This historical connection, layered with centuries of cultural exchange, underscores the deep yet often overlooked ties between India and Korea.

Today, these bonds continue to evolve. The Korean community in Chennai is the largest foreign national group in the city. During our travels in Korea, we were met with warmth and a shared sense of history. Cultural institutions, and specifically the InKo Centre, Chennai, foster vibrant cultural dialogue, bringing Korean art, literature, and creativity into conversation with Indian traditions.

Through Limits of Change, I hope to contribute to this ever-growing exchange, offering a lens into a lesser-known chapter of peacekeeping history while sparking new conversations about Indo-Korean relations, shared legacies and the role of storytelling in bridging cultures.

How does the story of the CFI and your father's experiences reflect the broader context of India's relationship with Korea at that time?

My father was among the handpicked officers of General Thorat’s Advance Party, that began the delicate process of peacekeeping in Korea, staying on to oversee preparations as part of India’s larger commitment to resolving the fate of non-repatriate prisoners of war. The task eventually brought 6,000 soldiers of the Custodian Force India to the front lines of history. Alongside them stood the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission, led by General Thimayya, navigating a diplomatic tightrope as world leaders feared that the unresolved POW issue could reignite conflict. Limits of Change revisits this crucial moment, exploring how India's role as a mediator shaped its relationship with Korea and contributed to the fragile yet necessary pursuit of peace.

What are your thoughts on the current state of the India-Korea relationship, and what role can cultural projects like "Limits of Change" play in fostering stronger ties between the two nations?

The vibrant currents of Korean cultural creativity have undoubtedly reached Indian shores, just as India’s rich heritage continues to inspire curiosity in Korea. During our visit, I was heartened by the warmth with which we were received and the genuine interest people expressed in India’s history and contemporary culture. Limits of Change aspires to deepen this cultural dialogue, bridging shared legacies that trace back to the time when the Indian princess journeying to Korea became Queen Heo Hwang-ok (32AD – 189AD). From those early bonds to the steadfast neutrality of the CFI peacekeepers, and beyond, our histories are intertwined in ways both historic and deeply human.Art and culture have a unique power to transcend borders, fostering empathy, imagination, and mutual understanding. Through this project, I hope we can cultivate a space for further collaboration and exchange - because when two countries or two civilizations engage in a dialogue through creativity, they don’t just exchange ideas; they truly see and understand each othe

How about this article?

- Like2

- Support0

- Amazing5

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful1