In both Korean and Iranian cultures, life is often seen as a sacred journey—one shaped by fate, family, and the choices we make. But what happens when someone decides to end that journey too soon? ‘Death’s Game,’ a recent Korean drama, dares to ask this question boldly and imaginatively.

When I first watched it, I expected a dark fantasy. What I found instead was a deeply human story—one that challenges us to see life through the eyes of others, even in their final moments. As the main character is forced to live and die in twelve different lives, each one more unexpected than the last, the drama becomes a mirror, reflecting not just Korean society but universal truths about regret, empathy, and the will to live.

Life After Despair: A Korean Reflection on Suicide

This K-drama opens with Lee Jae choosing death after losing his job—a moment that reflects the intense pressure many young Koreans face in a competitive society. On the other side, Iranian youth are navigating unemployment and societal expectations. However, the K-drama doesn’t glorify suicide but instead uses it as a turning point for transformation.

In both Korea and Iran, despair can feel isolating. But ‘Death’s Game’ reminds us that even in our darkest choices, there’s a chance to learn—if we’re willing to see life through others’ eyes.

Twelve Lives, Twelve Lessons: Empathy Through Rebirth

Lee Jae is forced to live 12 different lives—from a soldier to a celebrity, from a child to a criminal. Each life teaches him something new about pain, love, sacrifice, and injustice. This item mirrors the Iranian concept of “hamdardi” (compassion through shared experience).

The kdrama’s structure—dying and waking up in someone else’s body—is more than fantasy. It’s a call to empathy, something deeply rooted in Persian poetry and Korean storytelling alike.

The Role of Death: Not an End, But a Teacher

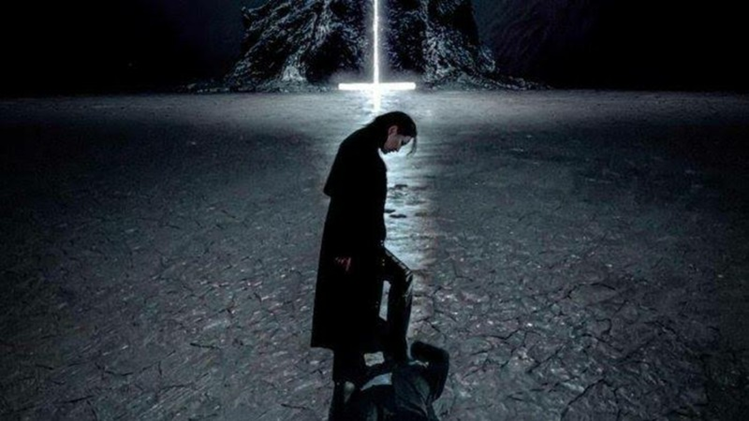

The character of Death (played by Park So-dam) is not evil but firm and philosophical. She challenges Lee Jae to reflect, not escape. Park So-dam’s portrayal of Death is enhanced by minimalist costuming and stark lighting.

She often appears in shadow or against neutral backgrounds, making her presence feel timeless and detached—yet strangely intimate. Her visual stillness contrasts with the chaos of Lee Jae’s lives, reinforcing her role as a guide rather than a villain.

In Iranian culture, death is often a poet’s companion—a reminder to live meaningfully. In ‘Death’s Game,’ Death becomes a mentor, guiding Lee Jae toward redemption.

Visual Storytelling and Emotional Impact

'Death’s Game' doesn’t rely on spectacle alone—its visual storytelling is deeply tied to emotion, character growth, and philosophical reflection. Each episode is crafted with cinematic precision, using lighting, framing, and pacing to mirror Lee Jae’s internal transformation.

Color and Mood

The drama shifts its color palette depending on the life Lee Jae inhabits. Cold, desaturated tones dominate his own life—especially in scenes of despair and isolation. But when he enters another person’s body, the colors often become warmer or more vivid, reflecting the emotional intensity of that life. This contrast subtly reinforces the idea that life, even when painful, is rich with meaning.

Symbolic Framing

Close-ups are used not just for dramatic effect but also to emphasize moments of realization. For example, when Lee Jae begins to understand the consequences of his actions, the camera lingers on his eyes—inviting viewers to see what he sees and feel what he feels. In Iranian cinema, this technique is also common, especially in films by a famous Iranian director like ‘Asghar Farhadi’, where silence and facial expressions carry the emotional weight.

A Drama That Crosses Borders—and Hearts

'Death’s Game' is more than a fantasy drama—it’s a philosophical journey that asks us to reconsider what it means to live, to die, and to truly understand others. Through its layered storytelling and emotional depth, it speaks to universal struggles: despair, empathy, and the search for meaning.

For Iranian viewers, the drama may feel surprisingly familiar. Its poetic reflections on fate, its critique of social pressure, and its call for compassion echo themes found in Persian literature and cinema. And like many Korean dramas, it doesn’t offer easy answers—only the invitation to reflect, feel, and grow.

In the end, ‘Death’s Game’ doesn’t just tell us to value life. It shows us how, through the eyes of strangers, the weight of choices and the quiet courage to begin again.

How about this article?

- Like2

- Support1

- Amazing1

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0