The Korean writer Han Kang won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2024, becoming one of the youngest recipients and with one of the smallest bodies of work among them. Yet, in a short time, she managed to capture the attention of the global literary community thanks to the complex human themes she addresses in a simple and fluid manner through her prose and poetry. This was not the first time she drew global recognition; she had already won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016 for her novel The Vegetarian. Thus, Han Kang became the first Korean author to achieve both distinctions.

Her Nobel Prize win was not a purely individual effort but rather the outcome of years of collective work in Korea to share its culture with the world, whether by governmental institutions, NGOs, or even individuals. Everyone worked toward a single goal regardless of political or ideological differences.

Walking through Han Kang’s literary universe is a journey through silence, suffering, and resilience. Han Kang is deeply preoccupied with humanity, the past, and memory. Although only five of her longer works are currently available in translation, one can clearly sense both the diversity of her themes and her unmistakable voice throughout them.

In this article, I will present my simple analysis of her five works and my overall view of her literary world.

In my opinion, Han Kang’s most important work is her novel Human Acts, though it receives less attention compared to The Vegetarian. The book had long been on my list after I read The Vegetarian, but Han Kang’s Nobel win pushed me to explore the rest of her works, Human Acts being the first.

The novel revolves around the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, narrating how the massacre affected various characters of different ages as the story moves between past and present. Some of the characters are closely linked, others meet only briefly, and still others remain mere names or anonymous faces in each other’s lives.

Han Kang presents the devastation of dreams and futures of many who simply sought justice and freedom, only to be met with brutal violence that claimed some lives and left others permanently scarred. You don’t need to be deeply versed in Korean history to engage with the narrative, a brief look at the Gwangju Massacre is enough for context. And even without it, you will easily find resonances with events from your own country’s history. The title Human Acts fits perfectly, as the book speaks plainly of human nature and how people interact with society and each other.

The cast spans different ages, genders, and cultural backgrounds, and Han Kang excels at giving each a distinct voice while maintaining narrative cohesion. The conclusion, in which she shares her own connection to the uprising through staying in the house of a victim, offers a glimpse into her inner world and the depth of her empathy. From a mere coincidence tying her to the tragedy, she crafted a whole universe that memorializes the victims, reminding us they were humans with dreams, not just numbers.

The novel is emotionally devastating. Though it merits multiple readings to fully grasp all the characters’ details, my first experience left me in tears and collapse. Even though the events took place in another country and time, they echo everywhere; such tragedies are inescapable.

While Human Acts is deeply political, The Vegetarian is far more intimate, centering on a single woman who suddenly decides to stop eating meat. This seemingly small choice unsettles everyone around her, spiraling into a larger crisis as she gradually decides to become a plant herself.

Her decision arises from lifelong repression and being treated as insignificant, a “convenient wife” chosen by her husband for her docility. The moment she made an independent choice, she faced harsh rejection and even violence. Later, she was exploited by her sister’s husband, a conceptual artist who reduced her body to a tool for his work. Ultimately, she becomes alienated from both herself and her body, confined within her mind.

This culminates in the final section, where her sister visits her in a psychiatric hospital. By then, the protagonist is fully convinced she is a plant, refusing food or movement. In this transformation, she protests the injustice and marginalization she endured; if others always saw her as invisible, she might as well merge with the earth itself.

The novel is experimental and surreal compared to the realism of Human Acts. While not fantastical, it borders on the uncanny, portraying an extreme psychological condition. I have read The Vegetarian three times already and still feel drawn to revisit it. Each reading reveals new layers of meaning.

The turning point that fully immersed me in Han Kang’s world was reading The White Book, a hybrid of fiction and memoir. Based on her own life, it is composed of fragmentary reflections and imaginative passages. At its heart is the death of her older sister, who passed away shortly after birth due to the lack of medical care available to her mother at the time.

Through these meditations, one understands why Han Kang can create characters with such raw honesty. She is acutely sensitive, burdened with guilt over the smallest things, perpetually mourning the world’s suffering, and often plagued by headaches. Yet she is not a gloomy or hopeless person. She coexists with sorrow, accepts the world as it is, and seeks to compensate for the forgotten and marginalized souls in her own way.

The atmosphere of Greek Lessons is lighter and more restrained than her previous works, though it remains one of my personal favorites despite its mixed reception among readers.

It tells the story of a woman who has lost her voice due to psychological trauma and a Greek teacher gradually losing his sight. Their relationship develops with extraordinary subtlety, with almost no overt action.

The novel contemplates silence, language, and the struggles of highly sensitive individuals in a materialistic world that undervalues emotion. These characters reflect Han Kang herself, and one can sense her own pain in theirs. The book is deeply lyrical, requiring patience and attention to detail. Entering its quiet world without expecting dramatic twists allows for a rewarding experience.

Han Kang’s most recent translated work is We Do Not Part, centered on two friends, a writer and a former photographer, whose lives diverge over time. The writer is compelled to travel to her friend’s hometown in Jeju after the latter is hospitalized, tasked with caring for her friend’s parrot.

The novel recalls the tragic Jeju Massacre of 1948 through archival material and the art project of the photographer, whose mother had been a silent witness to the atrocities and carried the pain throughout her life without ever speaking of it. As the protagonist writer stays in her friend’s home, she discovers hidden truths about both their relationship and this dark chapter of history, suspended between past and present, reality and imagination.

To me, this is Han Kang’s least compelling translated work so far. Though its subject and characters are powerful, the novel felt like a mix of elements from her earlier successes, without fully realizing any of them. Still, it is worth reading, and perhaps with time and rereading, my perspective will change.

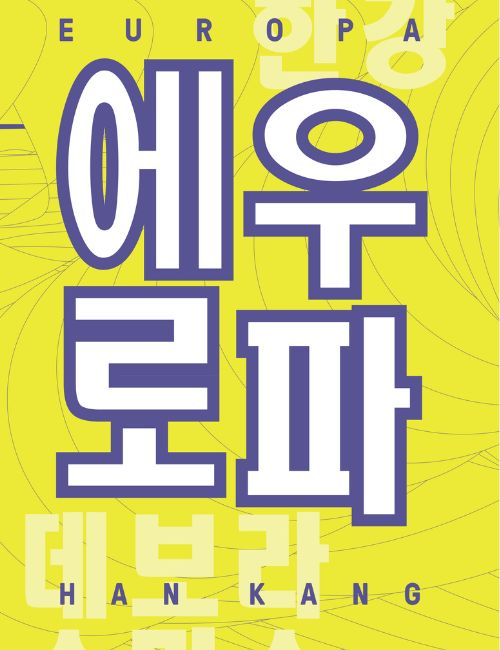

Beyond her five novels, there is also a short story titled Europa, available in translation.

It explores a complex relationship between a woman traumatized by a failed marriage and violence, and a man struggling with his gender identity, feeling he is a woman inside. Spanning only about 27 pages, it provides glimpses into their lives. Told from the man’s perspective, it captures his confusion and his simultaneous love for In-ah and desire to be like her.

The story offers only fragments about In-ah’s past abuse, as the narrator knows little. Their bond is unconventional; they do not interfere in each other’s lives, yet they provide mutual support when needed, free of judgment.

While Han Kang’s style shines more in longer works, Europa still presents a deeply human relationship, portrayed transparently and without confinement to stereotypes. As always, Han Kang prioritizes authenticity, creating characters who speak freely for themselves, urging readers to empathize and analyze on their own.

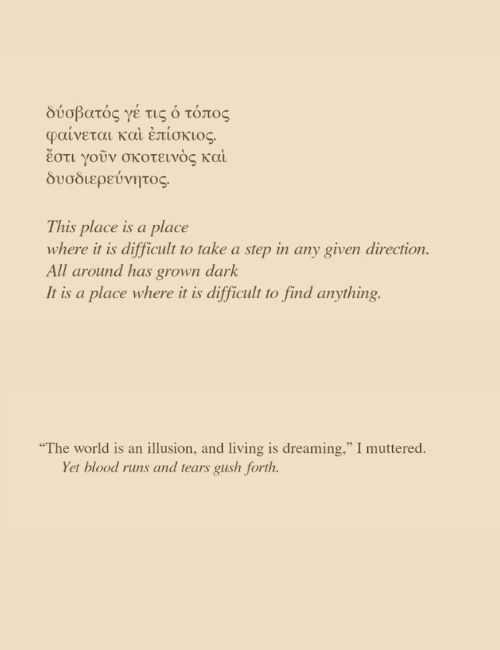

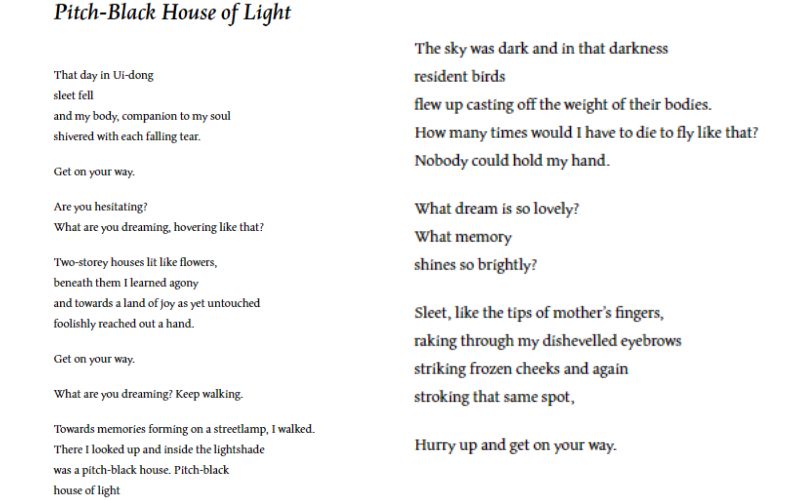

What many do not know is that Han Kang also writes poetry, with a few poems translated and published in various journals. No full poetry collection has yet been translated, but what is available is certainly worth exploring.

Contrary to what some might assume, seeking approval from other cultures through flattery or imitation never works. What endures is authenticity, the ability to convey reality with all its cruelty and beauty. Han Kang is a shining example of an honest writer, profoundly concerned with humanity and its struggles. She is not after fame or fortune, only the chance to give a voice to the voiceless.

Keywords:

Han Kang, Nobel Prize, Man Booker, The Vegetarian, Human Acts, Korean Literature, Korea Net, Republic of Korea

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0