[Translated][INTERVIEW] From Language Enthusiast to Professional Translator: A Conversation with Archana Madhavan on Korean Literature and the Essence of Translation

2025-08-29

Archana Madhavan is a Korean-to-English translator. Born in India and raised in the United States, Archana’s academic background was in science, yet her passion for Korean developed during her university years. Her curiosity drove her to learn the language, and through time and perseverance, she mastered it and chose to share her passion with others through translation.

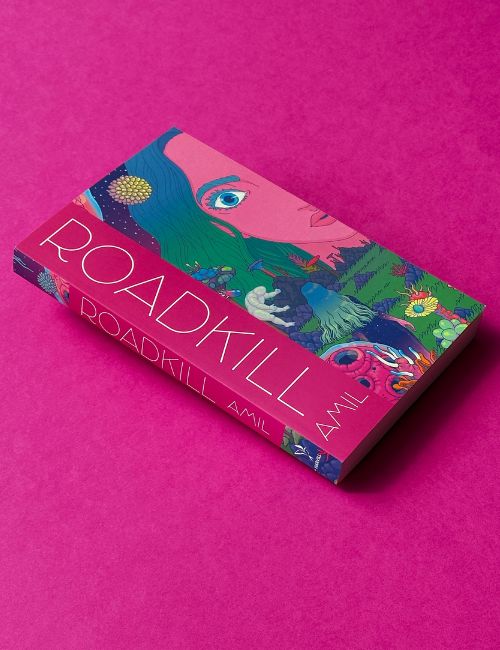

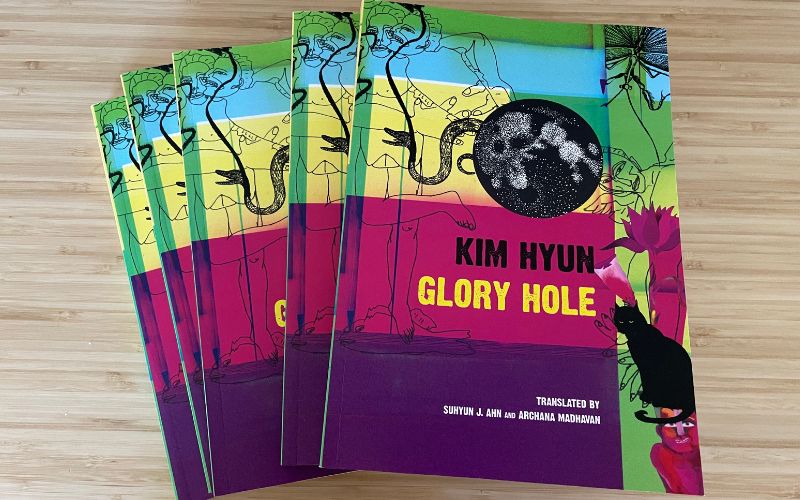

Archana began translating works of contemporary Korean literature in 2019. In just a few years, she has successfully translated a range of literary works across various genres. Her most notable translations include the poetry collection Glory Hole by Kim Hyun and the short story collection Roadkill by Amil, which was released earlier this August. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at her journey and her path to mastering Korean.

The interview was conducted via email between August 15 and August 28. The following are excerpts from it.

Could you tell us more about your beginnings and background? Why did you study science specifically? And what drew you to Korean literature?

I was born in India and grew up in the United States. English is the language I’m most fluent in, but my home language is Marathi. I also understand Tamil, have conversational knowledge of Japanese, and, of course, translate from Korean. I think I always felt an affinity toward languages and the literary arts.

In school, English and French were my best subjects, and I used to dream of being a writer, but my father really pushed me away from pursuing anything creative and insisted that I study science or engineering at university. At the time, I hated math, so I chose to study molecular biology on a whim, thinking maybe I’d work as a lab assistant or become a researcher someday.

I had excellent professors as an undergraduate and cultivated a genuine interest in the natural sciences, but academia really wasn’t for me. Instead, what I love is learning and teaching science. It took some time to get here, but outside of my life as a translator, I have a full-time career as an instructional designer developing courses and training in the field of data analytics.

My life as a translator really started from that unshakeable love of language I had since I was young. While I was studying science in college, I fell into Korean film and dramas and became really curious about how the Korean language worked; sometime in 2009-2010, I started to teach myself the language.

I never thought or aspired to reach any degree of fluency in Korean, nor did I have any particular goals for what I wanted to do with the language. I just kept following my curiosity and whims, I guess that’s been a pattern in my life! Eventually, I reached a level of proficiency that allowed me to read books and naturally found myself drawn to Korean literature.

What changed in these 6 years between your first translated poem and your latest translation, Roadkill? How did your style and working routine evolve?

When I first started translating, I think I was translating completely on instinct. That is, I don’t think I was really thinking about why I was making certain choices. Over the years, I’ve read several critical essays, translators’ notes, and other writing by experienced translators on their perspectives on the craft and role of translation, that’s helped me develop and articulate my own philosophy as a translator, which is allowing me to be very intentional with which projects I choose and my approach in translating them.

In your opinion, what are the differences between the translation process of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry?

I don’t think the translation process itself is very different between genres; it’s more the publishing process that’s different.

That said, I do think that to be able to translate across genres, you have to be well read in those genres, in both the source and target languages. The very best translators are incredible writers and poets in their own right. They have a deep understanding of craft, which I believe starts from being a prolific reader.

Do you think it is important to study the original author’s background before translating? How often do you contact the writers? Elaborate on your translation journey for Amil’s book Roadkill as an example.

To an extent, yes. I’m personally interested in translating female voices and other marginalized voices, so I gravitate toward writers with that background. I’m usually curious about how a writer got started, what other books they’ve translated, and what the reception has been to their other works. I’d also find it impossible to translate writers who oppose fundamental rights and freedoms that all humans deserve to have.

I would love to be personally acquainted with all the writers I translate, but that doesn’t always happen. I’m actually a lot closer to the poets I’ve translated than other writers. The poet Lee Jenny and I have met in person and exchanged numerous emails, messages, and phone calls over the years, discussing her work and my translation. On the other hand, I met Amil, the author of Roadkill, once over videoconferencing before the project, and then only contacted her again when I had a couple of specific questions about the text. We met in person for the first time when I visited Korea in July this year.

How do you balance your job, writing, and translating?

I really don’t. When I was translating Roadkill, I worked 14 hours a day and barely slept 5 hours a night for about 6 months. (In addition to Roadkill, I was working on other smaller translation projects and also served as a judge for the Lucien Stryk Asian Translation Prize in the same time frame. It wrecked my body completely.

I wrapped up two projects in the first half of this year and was much better about taking care of myself this time around. I learned that no matter how much work I have, it’s never worth sacrificing sleep or exercise.

Do you think translation can convey the true meaning and essence of the work? And how do you research before translation to understand the cultural context?

I think about this a lot. On the one hand, I reject the idea that some emotions or ideas are impossible to translate from one language to another. It might not be possible to find perfect equivalence at the single-word or sentence level, but I do think the core message of any work can be translated into another language. At the same time, translation often requires compromise, and in that process, some dimension or nuance of the source text might be lost. I like to think of a translated work as something original, co-created by the translator and the source text writer, at the intersection of both languages.

As for research, I usually search up articles in Korean when I encounter any terms or practices I’m not familiar with as I read the source text. I’m also lucky to have a great network of translator friends and a Korean language tutor whom I can ask as well.

Among your translated works, what is the closest to your heart and why?

Lee Jenny’s PIROWA PADOWA (Korean title: 아마도 아프리카), which won the 2024 Malinda A. Markham Translation Prize and will be published by Saturnalia Books later this year.

Lee Jenny’s poetry collection reminds me of why I started learning Korean in the first place.

From the very beginning, I was drawn to the Korean language because I loved the way it sounds, so I appreciated that Korean phonology was an important element in Lee Jenny’s work.

In many ways, PIROWA PADOWA is also emblematic of my growth as a translator. It’s the collection I translated during my ALTA mentorship in 2022, which played an important role in my education and training as a translator.

I learned how to give and receive feedback with this manuscript and learned how to pitch it and submit it to countless publishers. Because of it, I learned how to manage tricky conversations about copyright and contracts in both English and Korean. I also wrote my first-ever translator’s note for it. It’s an incredibly meaningful work to me because I share so many significant milestones with it.

How do you think translation can connect the different cultures? And how did your work in translation deepen your connection to Korean culture?

I think translated literature offers people the opportunity to learn about cultures, histories, and circumstances that are different from their own. Readers are also exposed to narrative structures and conventions that may be different from what they’re used to. But that said, I’d be hesitant to say that translation offers a connection to another culture. I think to truly understand a culture, it’s essential to learn the language(s) it operates in.

As someone who is not ethnically Korean and who doesn’t live in Korea, I would say I have knowledge of Korean culture, but not necessarily a connection to it. The connection I feel to Korean culture really comes from the relationships I’ve built with the Korean writers and translators I’ve worked with over the years.

What methods were the most useful in your Korean language learning journey? What is your advice to beginners in Korean?

I was a very auditory learner, so I learned a lot of basic Korean through podcasts and Korean radio shows, and by watching dramas and films, before I even learned how to read Korean. I think that actually helped me with pronunciation and spelling later on because I was already familiar with the sounds of the language.

As for my advice to beginners: there’s a lot of really terrible language content on social media these days. If you’re serious about learning Korean, learn with a teacher who is actually trained in teaching Korean as a second language. And don’t be afraid to embarrass yourself or make mistakes. The more mistakes you make, the more opportunities you have to learn!

What are your upcoming plans?

I have another translation coming out next year (if all goes well), and I’m working on a couple of other samples.

Archana Madhavan’s passion for translation and her curiosity about Korean culture are what helped her master the language and achieve her goals. Her journey is an inspiration for anyone who loves the Korean language and culture, as it takes patience, perseverance, and dedication to reach such a level. Translators with this kind of passion are the ones who allow us to gain insight into other cultures and break down barriers between people.

Keywords:

Archana Madhavan, Korean literature, Roadkill, translation, Korea Net, Republic of Korea

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0