Hwachae(화채) is a traditional Korean fruit punch or beverage made with fresh fruits, sweeteners, and sometimes floral or herbal ingredients. Known for its refreshing and light taste, Hwachae has been enjoyed in Korea for centuries, especially during hot summers and festive occasions. This drink varies in preparation, with historical and regional adaptations that reflect Korea's culinary evolution.

Historical Background

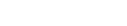

Hwachae dates back to the Chosun Dynasty (1392-1897), where it was initially served in royal courts and noble households. Early versions were simpler, often made with honey or sugar syrup infused with fruits like Asian pear, watermelon, or citrus. Over time, it became popular among commoners, who adapted the recipe based on seasonal availability.

For the historical background of Hwachae in the Chosun Dynasty:

Historical records, such as 《Jubangmun》 (주방문, 酒方文), a Chosun-era cookbook, mention early forms of Hwachae as a fruit-infused honey water served to royalty. Another key reference is 《Eumsik Dimibang》 (음식디미방, 1660), one of Korea's oldest cookbooks, which describes fruit-based beverages sweetened with honey or fermented grain syrup (jocheong).

For the references to Jubangmun and Eumsik Dimibang

During the Korean Empire (1897-1910) and Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), Western influences introduced new ingredients like soda and milk, leading to modern variations such as "Milk Hwachae" (우유 화채).

Hwachae Ingredients and Variations

Hwachae, a traditional Korean fruit punch, is a refreshing and versatile drink that combines a variety of fresh fruits such as watermelon, Korean pear, strawberries, peaches, and apples. The sweetness can be adjusted using natural sweeteners like honey, sugar, or jocheong (Korean rice syrup), while the liquid base can range from simple water to carbonated drinks or even milk for a creamier texture. To enhance the flavor and presentation, optional additions like pine nuts, a sprinkle of cinnamon, or edible flowers such as omija (Schisandra berries) and rose petals are often included. This delightful beverage can be customized to suit different tastes, making it a perfect treat for warm weather or festive occasions.

Cultural Significance of Hwachae

Hwachae holds a special place in Korean culinary traditions, deeply rooted in seasonal customs and celebrations. Primarily enjoyed as a cooling summer refreshment, it is served chilled to provide relief from the heat. The drink also plays a role in festive occasions, often prepared for Chuseok(Korean Thanksgiving) and the Dano Festival, where it symbolizes abundance and joy. Historically, Hwachae was even featured in royal court banquets (*궁중 연회*), highlighting its esteemed status in Korean cuisine.

Modern Adaptations of Hwachae

While Hwachae remains a beloved classic, it has evolved with contemporary trends, offering creative new variations. Sparkling Hwachae, made with Sprite or carbonated water, adds a fizzy twist to the traditional recipe. The Dalgona Hwachae emerged as a playful take inspired by the viral Dalgona coffee trend, incorporating whipped coffee flavors. For those seeking plant-based options, vegan versions using almond or oat milk have also gained popularity. These modern adaptations ensure that Hwachae continues to delight both traditionalists and adventurous food lovers alike.

Hwachae is more than just a drink-it represents Korea's seasonal culinary traditions and adaptability. From royal courts to modern cafes, its evolution mirrors Korea's history while maintaining its essence as a refreshing, fruit-based delight.

As the writers and reporters of this article, we aimed to explore Hwachae not only as a traditional beverage, but also as a cultural artifact that reflects Korea’s evolving culinary identity. By examining historical records, academic research, and contemporary interpretations, we found that this seemingly simple fruit punch embodies a rich intersection of seasonal customs, royal heritage, and modern trends. The research process strengthened our understanding of how food can bridge the gap between tradition and innovation. Through this work, we hope to offer readers a meaningful and refreshing insight into Korean food culture.

---

References:

- Han, B. (2010). *Korean royal court cuisine: History and culture*. Seoul: Kyomunsa.

- Kim, Y. (2015). *Traditional Korean beverages: From royal courts to tables*. Journal of Korean Food Culture, 30(2), 145-160.

-Kim, J. (Trans.). (2004). *Jubangmun: A study of Chosun-era royal recipes*. Seoul: Institute of Korean Royal Cuisine.

- Jang, G., & Hong, M. (Eds.). (2007). *Eumsik Dimibang: The oldest Korean cookbook (1660)*. Paju: Korean Studies Information

- Han, B. (2003). *Traditional Korean Cuisine*. Seoul: Hollym.

- 《Eumsik Dimibang》 (1660). [Original Chosun-era manuscript].

- Kim, Y. (2015). *Food and Korean Identity*. Cambridge University Press.

_ Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corp. (2020). *Korean Traditional Beverages*.

- Lee, S. (2017). *Seasonal Korean Cooking*. London: Phaidon Press

-Pettid, M. (2008). Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History. London: Reaktion Books.

- National Folk Museum of Korea. (2019). Korean Seasonal Festivals and Food.

- Kim, J. (2021). New Trends in Korean Drinks. Food Science Journal, 45(3), 112-125.

- Seoul Cafe Association. (2022). Innovative Korean Beverages Report.

Korea Tourism Organization. (2023). The Taste oKoreaf Korea: Traditional & Modern.

Korea Foundation. (2018). Korean FoodKorea Foundation. (2018). Korean Food: A Cultural Journey. Seoul: Seoul Selection.: A Cultural Journey. Seoul: Seoul Selection.

How about this article?

- Like13

- Support1

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful1