Juree Kim is a sculptor based in Seoul who works primarily with soil, water, and the passage of time. Her practice begins with observing the fundamental movements of the world, the way matter is formed and dissolved, and translating those changes and traces into a sculptural language. Rather than treating sculpture as a fixed, completed form, Juree explores it as a “living sculpture” that continuously reshapes itself through the forces of time and environment. She approaches sculpture not as a finished object but as an event of existence, one that is constantly eroding and accumulating. Through the self-dissolving nature of materials, her work reflects on the intertwined relationships between humanity, civilization, and the natural world.

Juree Kim’s artworks are held in prestigious public collections such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Henan Museum in Zhengzhou, China, the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art in Korea, and the SongEun Art and Cultural Foundation in Korea. Over the years, she has received numerous awards, including the Grand Prize at the 10th Song-Eun Art Award (2010), the Sovereign Asian Art Prize from Hong Kong’s Sovereign Art Foundation (2012), and the Creative Support grant from the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture (2022).

Her pieces have been featured in several exhibitions; in 2021, ‘’KOREA: Gateway to a Rich Past’’ at the Princessehof National Museum of Ceramics in Leeuwarden, Netherlands. In 2022, ‘’Ocolumns’’ at This Is Not a Church in Seoul, Korea, and ‘’Hot Spot’’ at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, Italy. In the following years, 2023/2024, her work was included in ‘’The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989’’ at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the United States. Most recently, she participated in the ‘’Irreverent Forms’’ exhibition at Gladstone in Seoul, Korea. She has also created works for major international large-scale art exhibitions, including the First Central China Ceramics Biennale (2016/2017), the British Ceramics Biennial (2017), and the Indian Ceramics Triennale (2018).

‘’Irreverent Forms’’ (Nov 20, 2025-Jan 3, 2026) is a group exhibition featuring Korean artists Juree Kim, Hun-Chung Lee, and Dan Kim. The exhibition challenges traditional ceramics, showing works that are imperfect, fragile, and constantly changing. Using dissolving clay K-houses, broken K-pots, and experimental forms, the artists explore change, memory, and the mix of tradition and modern ideas.

Below are excerpts from an email interview with Juree Kim on Dec 3-6 about her work with unfired clay.

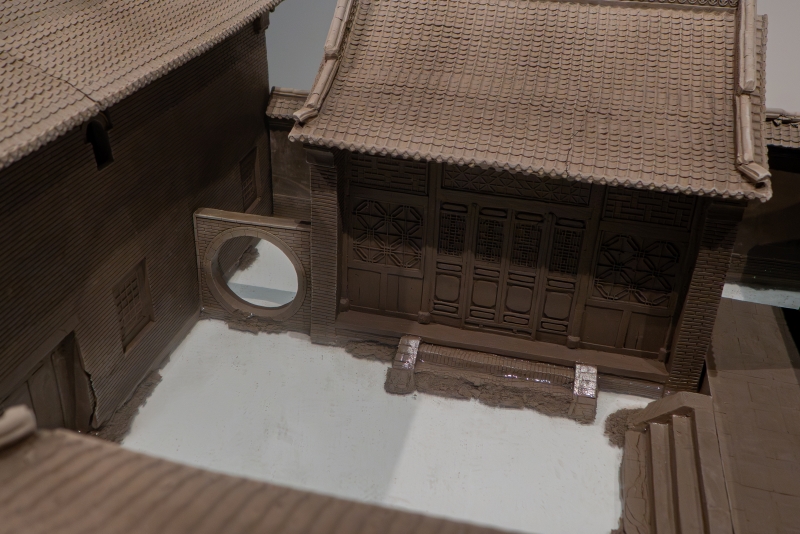

1. Why do you focus on old Korean houses in your sculptures?

My interest in old Korean houses began around 2008, when the ‘’Hwigyeong: Evanescent Landscape’’ series first emerged. At the time, I was living in Hwigyeong-dong, Seoul, and I witnessed entire clusters of old houses being demolished due to redevelopment. This experience made me realize that a house is not merely an architectural structure; its walls hold the time, emotions, and memories of the people who lived there. Re-creating these houses in clay became a way to work with the memory and temporality embedded in disappearing landscapes. In my practice, these old houses transcend architectural form and become a site for contemplating existence, disappearance, memory, and time. And, “Hwigyeong” carries a dual meaning: it refers both to the name of the neighborhood Hwigyeong-dong and to the idea of an Evanescent Landscape.

2. Why did you decide to work with unfired clay, and how did that choice come about?

When I was studying sculpture, I once tossed a small clay sketch into water without much thought. As the clay particles slowly dissolved and the form disappeared completely, I experienced a kind of sculptural revelation. It wasn’t the disappearance of the form that struck me, but the fact that the process of disappearing felt like a powerful sculptural event in itself. Since then, I have come to see change and dissolution as essential to sculpture, and unfired clay naturally became the most honest medium for expressing this perspective. Unfired clay reveals the forces of time, natural cycles, and material transformation without resistance, showing sculpture as something that changes on its own.

3. What is the message you want to convey through the ‘’Evanescent Landscape’’ series?

‘’Evanescent Landscape’’ series was created by observing landscapes where existence, disappearance, and the traces of civilization gradually fade. I wanted to present “disappearance” not as destruction or finality, but as a point at which another possibility begins to open. The houses made of clay collapse and lose their form when they meet water, recalling the Buddhist and East Asian philosophical concept of impermanence (無常), the idea that all beings dwell for a while, change, break apart, and return to the flow of nature.

I hope the work prompts viewers to ask themselves: “What is this world made of, and how do things shift into another state?” For me, disappearance is not a loss but part of a larger cycle, a passage of life that exists beyond visible form. Through the subtle movements of clay and water, I try to reveal those quiet flows as honestly as possible. That is the essence of Evanescent Landscape.

4. Besides old Korean houses, have you made sculptures of other kinds of buildings?

The “Hwigyeong House-Evanescent Landscape” series, which I have worked on for many years, is based on mass-produced residential buildings from the 1970s–80s in Korea. This work stems not from an external sociological analysis but from an internal awareness shaped by living within rapid environmental and social changes. The multi-unit houses built on the outskirts of Seoul, outside the 1970s urban planning frameworks, are anonymous yet offer a radical lens for understanding structural shifts in Korean society.

More recently, I have been working with forms inspired by high-rise apartment complexes, which now dominate contemporary Korean cities. I have also created works based on architectural contexts from outside Korea, including: late Qing-dynasty houses in Qingdao, China, Falcon Pottery and workers’ housing in Stoke-on-Trent, UK, architectural motifs found in historic structures in Jaipur, India, and the rowhouse typology from Philadelphia, USA. These structures may not be monumental landmarks, but they carry the quiet layers of everyday life and the histories of ordinary people. I am drawn to these overlooked architectural strata, places where the deepest traces of life accumulate, and how they encounter the materiality of clay to reveal new relationships and possibilities.

5. What do you want people to think about when they see the houses made from unfired clay dissolve in water?

One of my works is titled ‘’Impermanence,’’ which refers to the cycle of arising and passing away. It deals with how a single life comes into being, stays for a while, disperses, and returns to the soil. Likewise, the dissolution of the clay houses is not meant to depict destruction, but the process of reintegration into natural cycles. I do not see collapse as an ending; rather, it contains a quiet transition to another state. I hope that watching this moment becomes a small contemplative pause, a chance to reflect on how we perceive the world and its changes.

6. Tell us a few words about the ‘’Irreverent Forms’’ exhibition in Seoul

‘’Irreverent Forms’’ is an exhibition that brought together three artists from different generations, each interpreting the fluidity and transformability of clay through distinct sculptural languages. Hun-Chung Lee questioned the values of traditional ceramics, while Dan Kim explored spontaneity and transformation as extensions of identity. The exhibition highlights how a single material, clay, can expand into diverse forms across generations and perspectives.

For me, it was a meaningful opportunity to present ‘’Hwigyeong-Evanescent Landscape’’ again in Korea, along with my recent ‘’Clay Tablet’’ series. ‘’Clay Tablet’’ began with the sedimentary traces left as clay settles in water, which I interpreted as material memories, unrecorded languages or fragmented scripts of a dissolved civilization.

By compressing these remnants into tablet-like forms, I sought to bring together the opposing forces of “recording” and “erosion” on a single surface. Rather than creating new shapes, the work is closer to reading the sensorial and stratified grammar that emerges where form has vanished.

Showing ‘’Hwigyeong-Evanescent Landscape’’ and ‘’Clay Tablet’’ together was a significant moment for me, as it revealed how time, trace, memory, and erosion form a continuous thread throughout my practice.

7. What do you enjoy most about your work?

I feel the greatest joy in moments when a work feels “complete,” not when it is finished by my hands, but when it begins to act according to the logic of the earth itself. When a house made to dissolve actually melts into water, when compacted clay breaks free from its mold, or when wet clay spreads across a surface like a new skin, these moments stay with me.

The deepest pleasure comes when the material behaves beyond my prediction. Water alters the surface of clay; rain and wind carve the forms anew; the sculpture rewrites itself. In those moments, the work feels like a being that transforms on its own. These experiences remind me that sculpture is not something I make alone, it is an event co-created with larger natural forces. That sense of collaboration with the world gives me the greatest joy.

8. What’s next?

I am currently expanding a long-term outdoor project that observes how clay sculptures weather over time. By translating the surfaces and traces left after the clay disappears into new sculptural languages, I approach sculpture not as a fixed object but as an event that unfolds within time.

This year, I have further developed this interest through the long-term project ‘’Weathering–Wolsan’’ in Dapnae-ri, Hwado-eup, Namyangju. Once a transitional landscape between Seoul and the surrounding farmland, the area is now designated for a GTX-B train depot, and its terrain and vegetation are on the verge of significant transformation. ‘’Weathering–Wolsan’’ documents soil sculptures as they are eroded and deposited by rain, wind, humidity, and plant activity, revealing the intersection of natural time (weathering) and civilizational time.

In parallel, my ‘’Desert’’ series explores how post-industrial remnants, ash, brick fragments, sand, and metal, return to an earth-like material state. This work also aligns with my ongoing inquiry into how time operates within matter.

As part of my upcoming activities, I am preparing for group exhibitions at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) and Thaddaeus Ropac Seoul in early 2026.

Juree Kim keeps innovating in ceramics, making works that are meaningful and thought-provoking.

How about this article?

- Like2

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0