Korea’s artistic heritage is admired around the world for its deep symbolism, refined aesthetics, and harmony between nature and human emotion. From the understated elegance of celadon and white porcelain, to the dynamic lines of Korean calligraphy, to the rhythmic passion of pansori, traditional Korean arts continue to inspire global audiences. Among these traditions, minhwa—Korea’s folk painting—holds a special place. These works, created by ordinary people, express wishes for happiness, longevity, protection, and prosperity. With their vivid colors, imaginative symbolism, and playful storytelling, minhwa has become one of Korea’s most recognizable and beloved art forms internationally.

Today, many contemporary artists reinterpret minhwa to connect tradition with modern life, bringing Korean cultural identity into new global conversations. Shin Meekyung, is one of these important voices. Her work preserves the spirit of classical folk painting while exploring new themes, materials, and expressions that resonate with audiences today. Her artistic excellence was recognized on a national level when her piece “잃어버린 것에 대하여” (On What Was Lost) received the Grand Prize at the 20th National Minhwa Competition. The judging committee praised her work for “its creative use of materials, expressive power, and color palette,” noting that Shin Meekyung captured “the enduring strength of women in the Joseon era” with remarkable depth. Established in 2010 alongside the opening of the Museum of Korean Folk Painting in Yeongwol, the National Minhwa Competition is one of the most prestigious events in the field. Winners receive not only a monetary prize but also the Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism Award, underscoring the cultural importance of their achievement. Artists like Shin Meekyung play a vital role in introducing Korean traditional arts to the world. Through their creativity, dedication, and reinterpretation of heritage, they help global audiences discover the richness of Korean culture and understand its connection to contemporary life.

With this achievement and her growing influence in the contemporary minhwa scene, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to speak directly with Shin Meekyung. Our conversation offered a deeper look into her artistic vision—how she approaches tradition, where she finds inspiration, and how she hopes her work will connect with audiences both in Korea and around the world. Through this interview, she shares not only her creative process but also her thoughts on the cultural meaning of minhwa in modern times.

This interview was conducted by email from June 11 to August 26, 2025

Can you please introduce yourself and tell us how you first became interested in Minhwa, the traditional Korean folk painting style?

I majored in crafts at university and later completed my master’s and doctoral studies in interior design and architecture. After graduating, I worked at a museum exhibition design company, where I was responsible for finding ways to display and interpret Korea’s traditional cultural heritage. Through this work, I naturally grew closer to traditional painting, and after leaving the company, I began studying minhwa in earnest, which eventually led me to the path of becoming an artist. The first time I became captivated by minhwa was when I encountered a chaekgeori (bookshelf painting) at a museum during my time at the company. Unlike Western linear perspective, the freely used reversed perspective and multi-view composition arranged books and objects in a way that was both elegant and delightfully playful. That sense of freedom and humorous spirit left a deep impression on me and gently drew me into the world of minhwa. Minhwa is more than decorative painting; it is a unique artistic language that expresses hopes, wishes, and wit. Within it, I discovered minhwa as an art form that contains life itself. Rather than aiming for realistic representation, minhwa holds the spirit of its era and the records of everyday life. This characteristic fascinated me even more, and I felt a sense of responsibility to carry forward its vitality in a language that speaks to the present. In my work, I focus on respecting the spirit of traditional minhwa while layering it with a contemporary sensibility and my own narrative. I reinterpret the objects in chaekgeori using items from modern life, apply modern colors and compositions to motifs such as tigers and peonies, and even experiment with combining minhwa with new media such as media art. To me, minhwa is not simply the restoration of a past legacy. It is a window that reflects both today and the future, and a process that proves the spirit embedded in tradition is still relevant in this moment. I hope my minhwa can exist as a bridge that connects the past, the present, and the future.

What draws you most to Minhwa as an art form, and how do you approach blending traditional techniques with contemporary themes?

For me, the greatest charm of minhwa lies in its freedom and wit. Minhwa is not an authoritative art form; it is a painting tradition filled with the imagination and hopes of ordinary people. Within its simple lines and vibrant colors are hidden wishes for life, humor, and satire. I believe that this honesty and warmth are what allow minhwa to resonate with audiences today. Whenever I encounter minhwa, I feel a sense of familiarity and comfort. It does not rely on technical grandeur or authority; instead, it expresses genuine human emotion. The symbolic elements—books and objects in chaekgeori, tigers, peonies—are not mere decorations. They reveal inner desires such as courage, abundance, and happiness. That is why I aim to honor these traditional meanings while ensuring that the emotions and experiences of people living today can also be reflected within them. In my work, I continue traditional techniques but add modern interpretations through color and composition. I maintain the strong, vivid palette of traditional minhwa while infusing it with today’s sensibility so that viewers can relate to the pieces in their everyday lives. Rather than simply reproducing motifs like tigers and peonies, I place them within the landscapes and feelings of contemporary society to create new narratives. This is the core of my artistic approach. For me, tradition and modernity are not opposing forces—they illuminate and expand one another. Minhwa is not a painting confined to the past; it is an art form that breathes in the language of today and can continue into the future. I believe deeply in that possibility, and through my work, I hope to keep opening new paths for the minhwa of tomorrow.

What aspects of traditional Korean art inspire you the most when creating your own works?

What inspires me most deeply in Korean traditional art is its naturalness and symbolism. In minhwa, there exists a world far beyond simple decoration. The peony symbolizes splendor and prosperity; the tiger embodies dignity and humor; and chaekgeori reflects a longing for wisdom and learning. I constantly find new inspiration in the way everyday life and heartfelt wishes are expressed through these images. The freedom inherent in minhwa is an important starting point for my work. Even when the proportions are exaggerated or the colors rendered boldly, the paintings contain sincerity and the warmth of life. I hope to carry this honesty and boldness into my own work through a contemporary lens. In my practice, I honor the traditional forms of minhwa while integrating digital media and modern objects to reflect the sensibilities of today. Through this approach, I want to show that minhwa is not merely a relic of the past but a living art form capable of expressing the present. The symbolism, freedom, and timeless expressive power of minhwa—these are the elements of Korean traditional art that draw me in most strongly and remain the driving force behind my work.

How has your artistic style evolved over the years, especially as you integrate modern elements into a folk art tradition?

Korea’s folk art traditions have long been an expression of everyday hopes and humor. Symbols such as the tiger, magpie, and peony in minhwa were never mere decorative motifs—they carried human wishes and stories within them. As time passed, these traditions began to move beyond simple preservation and found new life through modern reinterpretation. From the 1980s onward, artists reimagined the colors and symbols of minhwa in contemporary painting, installation art, and design, allowing tradition to be reborn in the language of the present. By the 2000s, these efforts to bridge tradition and modernity had expanded onto the global art stage. Folk art became an essential foundation for shaping the unique identity of K-Art. Traditional materials—such as powdered pigments, hanji paper, and mineral colors—were combined with digital media and mixed materials, evolving into a new visual language. Today, K-Art has moved beyond merely reproducing tradition; it has become an art form that reflects contemporary life and emotion. The symbolism and vibrant color palette inherited from folk art remain at its core, serving as a source of originality that allows Korean contemporary art to shine distinctively on the world stage.

Your art seems to balance between preserving tradition and innovation - how do you maintain that balance?

For me, art has always been a dialogue between tradition and innovation. To paint minhwa is not simply to imitate old techniques—it is a process of calling forth the spirit and emotion contained within them and reinterpreting them through the sensibilities of today. In my work, I try to maintain that balance through both respect and variation. I honor the symbols and techniques of tradition, but I do not leave them unchanged. Instead, I layer them with the language and materials of the era I live in. For example, I reinterpret the objects in chaekgeori using contemporary items, or reconstruct tigers and peonies with modern colors and compositions. This allows me to breathe new life into traditional structures without breaking them. Furthermore, I explore various media beyond painting—such as media art and augmented reality (AR)—so that audiences can experience minhwa in ways that feel familiar yet newly reimagined. What I am always conscious of is that tradition should not remain confined within a museum—it should be an art that lives in the present. That is why my minhwa is not a reproduction of the past, but an open conversation directed toward the present and the future. By grounding my work in tradition while embracing contemporary sensibilities and experimentation, I continue to search for a harmonious balance between heritage and innovation.

How do you see the role of Minhwa and Korean traditional art in the global art scene?

Minhwa and Korean traditional art serve today as a bridge connecting cultural identity with a universal artistic language on the global art stage. As a form of everyday art that captures daily life and aspirations, minhwa reaches audiences beyond time and place through humor and symbolism. It does more than convey uniquely Korean elements—it becomes a window through which universal values and emotions can be shared. Moreover, Korean traditional art continues to open new possibilities through reinterpretation by contemporary artists. When traditional techniques and symbolic motifs are combined with modern contexts, the global art community comes to recognize them not as merely regional styles but as significant contributions to contemporary artistic discourse. Thus, minhwa and Korean traditional art both preserve the legacy of the past and, through modern experimentation and creation, establish themselves as a multilayered and expansive artistic language in the world. This dual role forms a vital foundation for Korean art to engage actively with the global art scene while asserting its unique voice.

What projects or themes are you currently exploring in your art?

Recently, I have been exploring ways to bring minhwa beyond traditional formats and into new media. One such endeavor involves collaborating with AI. Artificial intelligence reinterprets traditional motifs in ways I could not have imagined, presenting familiar tigers or peonies with entirely fresh sensibilities. Through this process, I have been able to view the possibilities of minhwa from a broader perspective and experience how it can be reborn within a contemporary aesthetic.Another project involves minhwa carved on woodblocks. The repeated process of carving, inking, and printing on paper creates subtle variations and traces that give my work a unique resonance. The tactile sensation and materiality inherent in woodblock printing add a depth and warmth to my pieces that digital work alone cannot achieve.Although these two approaches may seem different, they converge on a single question:

“How can minhwa live and breathe today?”

I seek to explore minhwa across the boundaries of painting and media art, discovering how it can preserve tradition while speaking in a contemporary language. I hope my work can serve as a small bridge connecting the past, present, and future.

Could you share about your personal exhibitions? What themes or messages do you focus on, and how do you decide what to present in these shows?

Exhibition: “Time Between / Accumulating Memories”

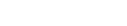

This work begins with the traditional chaekgeori of minhwa and unfolds through my own perspective and memories, layering tradition and creativity, personal recollections, and time to create a narrative. Chaekgeori is a genre of traditional minhwa that arranges objects symbolizing scholarship, knowledge, and material abundance in a visually structured way. In my work, however, the chaekgeori space becomes more than a display—it transforms into a landscape where my memories, daily life, and traces of the environment intersect, fracture, blur, and overlap. The process of layering my own language onto the traditional form of minhwa allows past and present, as well as individual narratives, to intersect, forming new layers of storytelling. This layering mirrors the way time accumulates and memories take shape. I follow the flatness and symbolism of traditional minhwa, but add processes of overlapping, spreading, erasure, and stamping. As a result, the compositions become landscapes where order and chaos, tradition and personal memory, and the boundaries of time intersect. The objects in the chaekgeori are no longer mere items—they are traces left on the surface of time and metaphors for disappearance, reborn through the work. Materials and techniques are equally crucial in conveying these concepts. The works are created on traditional Korean paper (jangji) using powdered pigments (bunchae), enhanced with woodblock printing. Over time, the texture and color of jangji naturally deepen, while the granular quality and color of bunchae help visualize the layers of memory. The repetition, stamping, and traces of the woodblocks express the materiality of time and memory. Ultimately, the chaekgeori in my work does not simply reproduce historical symbols; it expands into a “space of memory,” where my time, experiences, and contemporary traces overlap and permeate.

Through this work, I ask myself:

What remains, and what disappears?

How are memories accumulated and flowed?

In what ways does tradition connect with my present?

How about this article?

- Like0

- Support0

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0