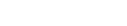

Korean glass artist Seon Min Park explores the passage of time and cultural continuity through the medium of glass. Her recent installation, presented at the APEC Exhibition titled “Scent of Korea in Silla” at Gyeongju’s Solgeo Art Museum (Oct 22, 2025 - Apr 26, 2026), reinterprets Silla’s Buddhist relic culture and Silk Road exchanges through contemporary glass forms. Comprising 262 individually hand-blown glass pieces, the work references sarira bottles, reliquaries, glass beads, and Roman glassware excavated from Silla tombs. It visualizes how ancient beliefs and cross-cultural exchanges can be reborn through light connecting Silla’s luminous heritage with the global ideals of coexistence and dialogue embodied by APEC. While her earlier “Re:Bottle” Project focused on sustainability and the reuse of discarded glass, this exhibition expands her inquiry into the spiritual and aesthetic continuity of Korean glass, revealing glass not as a material of consumption, but as a vessel of time, memory, and cultural connection.

Park Seon Min’s accolades include the Chairman’s Award at the 2020 DDP Design Fair, finalist recognition at the 2022 Gyeonggi Craft Competition, and the Special Award for Wood Craft at the 6th Kyungnam Industrial Design Exhibition in 2003. Some of Park Seon-min’s notable exhibitions include “Threading the Flow of Time” (WOL Samcheong, Seoul, 2024), “Perspective” (Sikmulgwan PH, Seoul, 2021), and “A Time of Smoothness” (Sagye Life, Jeju, 2020), along with several others.

The following are excerpts from a Nov 3 email interview with Seon Min Park, where she discusses her work and the glass installation ‘’Threading the Flow of Time: The Glass Sutra'' for the APEC Exhibition at the Solgeo Art Museum.

1. Please tell us about yourself and what led you to become an artist.

I am a glass artist who explores the coexistence of visible and invisible values through the medium of glass, a material that embodies both transparency and timelessness. I was drawn to glass for its innate charm, its ability to hold light and memory, and the way it preserves traces of time without change. My creative process begins with touch, shaping and layering the material until emotion and form become one. Building on various glassmaking techniques, I present works that explore the materiality of glass through two main directions. One focuses on artistic inquiry rooted in traditional craftsmanship and sculptural form, while the other experiments with contemporary techniques and recycled materials to expand the sustainable possibilities of glass.

Since 2014, I have been leading the “Re:Bottle” Project, transforming discarded glass bottles into new works that bridge the historical essence of ancient glass with the contemporary value of sustainability. Through this practice, I seek to connect the past, present, and future, continually redefining the role of craft in modern society and creating editions that convey meaningful messages.

2. What inspired you to start the “Re:Bottle” Project and focus on transforming discarded glass bottles?

The “Re:Bottle” Project began in 2014 during an exhibition in Jeju Island, a place where the cyclical rhythm of nature deeply influenced my perspective. I began to reflect on how industrial materials, once used and discarded, might re-enter the cycle of life through art. Glass can endure for tens of thousands of years without losing its form, yet it can be endlessly melted and reborn.

This paradox permanence and regeneration became central to my practice. During my research on ancient Korean glass artifacts, I was struck by how ancient and modern glass share the same material essence. This philosophy evolved into the “Re:Bottle” Project and the “Threading the Flow of Time” series, culminating in my APEC installation at the Gyeongju Solgeo Art Museum, a composition of 262 hand-blown glass pieces inspired by the Silla stone pagoda and sarira bottles. I also studied Roman glassware and numerous glass beads excavated from Silla tombs, revealing how glass was once among the most sacred and precious traded materials.

3. Are there specific traditional Korean bottles or glassware that inspire your work?

My works are inspired by sarira bottles, reliquaries, glass beads, and Roman glassware that entered Korea through the Silk Road. These relics are not merely functional or decorative objects; they embody faith, exchange, and aesthetic philosophy. Within them lies the idea of time being enshrined within matter, expanding sacred eternity into a reflection on continuity.

At the same time, I am deeply influenced by the subtle elegance of traditional Korean vessel forms such as the maebyeong (plum bottle), moon jar, and white porcelain jars, whose restrained lines and balanced proportions carry a quiet warmth. I also find inspiration in the everyday objects exhibited at the National Folk Museum,

Gyeongju National Museum, and the National Museum of Korea, vessels, jars, and containers shaped by the human hand, expressing a time when life and craft were

seamlessly intertwined. These forms are not relics of the past but timeless expressions of human proportion and emotion. Through glass, I reinterpret their essence, translating Korean aesthetics into a contemporary language of light and material, where time, memory, and spirituality coexist and flow together.

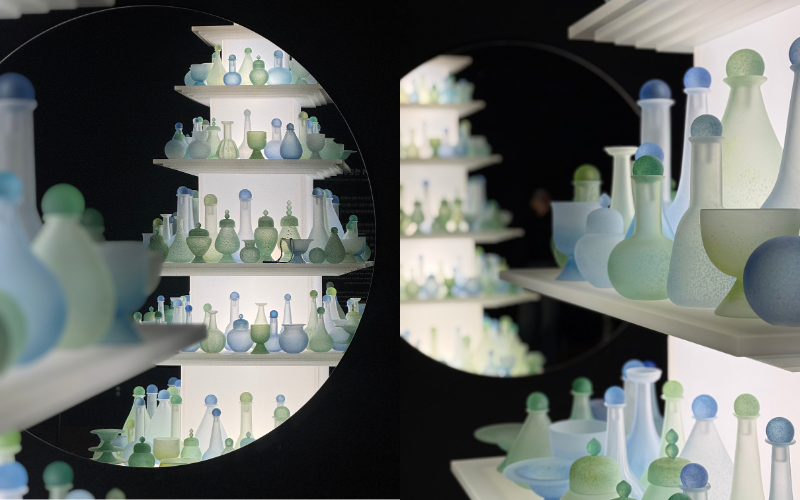

4. Why are green and blue prominent in your works?

The recurring green and blue hues in my works originate from my research on ancient glass artifacts. Excavated relics show that most ancient glass was made in deep cobalt blue and greenish tones derived from iron and copper oxides. These colors were not merely aesthetic choices they were the result of technological and geographical conditions of the time. For instance, blue glass was produced using cobalt ore imported from Central and Western Asia, a precious pigment that traveled eastward along the Silk Road. In contrast, green glass was typically made from sand containing natural iron impurities, making it a more regionally accessible and utilitarian color. I view these hues not simply as decorative elements, but as symbolic languages embedded in material and culture.

Blue represents divinity, spirituality, and the heavens, while green embodies nature, vitality, and renewal. Together, they express the flow of time and the cycle of life, where blue symbolizes eternity and spirit, and green conveys matter and regeneration. Their harmony visually manifests the central theme of my practice “Threading the Flow of Time.” Ultimately, these colors serve as symbolic continuities, linking the material and technological traces of ancient glass with the aesthetic language of the present. Through them, I seek to express the moment when ancient light seeps into contemporary time, where material, history, and emotion converge within the transparency of glass.

5. How many bottles were used in the APEC installation at Gyeongju’s Solgeo Art Museum, and what influenced your designs?

The installation consists of 262 individually hand-blown glass pieces, crafted from professional art-glass materials using tools and raw materials imported mainly from the United States. Its forms are inspired by sarira bottles, reliquaries, glass beads, and Roman glassware, each symbolizing faith, time, exchange, and culture, bridges between ancient and contemporary worlds.

The pagoda represents the accumulation of time, while the sarira bottle is a vessel that contains it a metaphor for time enshrined within matter. A glass-bead necklace made by melting discarded bottles into ancient bead forms was also displayed, serving as a symbolic bridge between the “Re:Bottle” Project and the APEC installation. Ultimately, this work represents a sculptural flow of light embodying the shared philosophy of connection and coexistence, linking the Silk Road of Silla with the APEC of today, a dialogue between light, culture, and time.

6. How do you think your work resonates with viewers at events like the APEC exhibition?

Many visitors described my installation as “a quiet flow of light and time.” That phrase captures the essence of what I wished to convey. Glass embodies both fragility and endurance, allowing viewers to experience time not as passing, but as cyclical. This flow connects Silla’s cultural exchanges along the Silk Road with APEC’s vision of global cooperation.

Though centuries apart, both share the same spirit, understanding through exchange, prosperity through connection. Ultimately, this work visualizes the philosophy of connection and coexistence shared by both the ancient Silk Road and modern APEC a luminous flow where past exchanges extend into the future.

7. What are your future plans?

My future work will continue to be grounded in the practicality of craft, while expanding into a multi-layered artistic realm that connects cultural heritage with contemporary society. I seek to reinterpret ancient glass artifacts and traditional Korean forms in today’s visual language, exploring how the aesthetics and wisdom of the past can be revived in the present and extended toward the future. Researching ancient glass is not merely an academic pursuit of historical facts, but an inquiry into the exchange, faith, and aesthetics that shaped each era. By integrating this research foundation into my creative process, I aim to expand a space where craft, art, and humanistic interpretation intersect. I hope my work will serve as an artistic record that mediates time and memory, bearing both aesthetic and intellectual depth.

Furthermore, through international exhibitions and cultural dialogues, I aspire to share the subtle beauty and sensibility of Korean aesthetics with a broader global audience.

Through these encounters, I hope glass will continue to serve as a “sustainable art of time” a medium that connects the past and present and carries its meaning forward to future generations.

How about this article?

- Like1

- Support1

- Amazing1

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0