[Translated]From Korean’s Roots to Readers’ Bookshelves Worldwide: A Journey of Writing and Identity – Interview with Ginger Park

2025-09-11

Reading is the gateway to knowledge and understanding. It sparks the imagination, strengthens memory, and goes beyond being a mere hobby—it has the power to touch hearts. Books are more than just pages; they open windows to other worlds, allowing us to explore different cultures and acting as a bridge between the past and the present. Through reading, we connect with our identity and heritage, gain insight into our roots, and discover the experiences of others. Stories thus become a powerful way to connect generations and foster a deeper understanding of oneself and society.

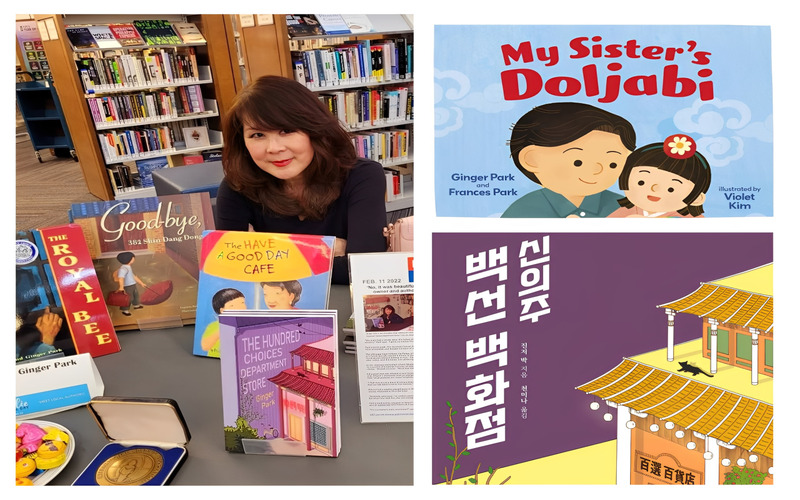

In this context, we turn to the author Ginger Park. Drawing from her Korean roots while living in the United States, she has carved out a distinguished place in the world of children’s literature, bringing the legacy of her heritage to readers across the globe. In this interview, we explore Ginger’s life as a Korean-American, her professional journey, and her latest works.

The interview was conducted via email from August 26 to September 3.

-Could you briefly introduce yourself to our Korea Net readers and tell us how your cultural background has influenced your writing?

Hello Korea Net readers! I’m delighted to be here today to share my world of words with you. So, a little about myself: I’m an award-winning author of many children’s books that foster the love of family, community, and history. My books often introduce children to more weighty topics, but they are always written to engage and prompt readers to ask questions.

While I was born and raised in Washington, DC, my books always reflect my Korean heritage, many of which are inspired by my family roots.

My parents and the eldest of my siblings immigrated to America in 1954, post-Korean War, settling in the DC area in 1959. My dichotomous life—daughter of Korean immigrants and All-American girl—was a blessing.

As a child of the late 60s and early 70s, we spent many summers in Seoul where my father’s family lived. Even though economic growth was booming with each visit, remnants of the Korean War remained, and those memories have stayed with me: memories that are a powerful tool for my writer’s soul.

-What inspired you to start writing children’s books that focus on Korean identity and culture?

As a child, I never dreamt about being a writer; rather, writing found me while I was healing from loss. Books for kids would come later, but the process was organic. When I was a teenager, my father suddenly passed away, leaving me cratered. My father was my light, and when he left me, I went through a very dark period. I was terrified of losing my mother, too, clinging to her like a koala bear to a tree, fearing our time together was on a clock. During those dark days, I realized I knew very little about my parents’ lives growing up in Japanese-occupied Korea. I was feverish to learn about my roots that spanned the Korean peninsula from Sinuiju to Seoul. I feared if I didn’t start asking questions, my history—like my father—would be buried forever. My mother, however, wasn’t a linear storyteller, so I started documenting my parents’ life events that culminated with the Korean War. I found myself ruminating over their harrowing childhoods, and it dawned on me that my parents’ universal stories of love, bonds, and resilience might interest children from all walks of life.

-What Korean traditions or customs did you grow up with that you still practice in your daily life in the U.S.?

Of all the holidays, Chuseok is the most cherished in our home. Every September, our mother would sigh with a faraway look in her eye, “Chuseok is coming.” That was our cue to hop into the car and drive to the duk-jip, craving our mouthwatering favorites: songpyeon, injeolmi, yeongyang-chaltteok, and japchae. On our way, my mother would share memories of childhood Chuseoks in Sinuiju; stories so vivid many have found their way into my books. My mother passed away in 2019, but we carry on with tradition, honoring her with our own memories

-You’ve co-written several books with your sister Frances. What do you enjoy most about collaborating with her?

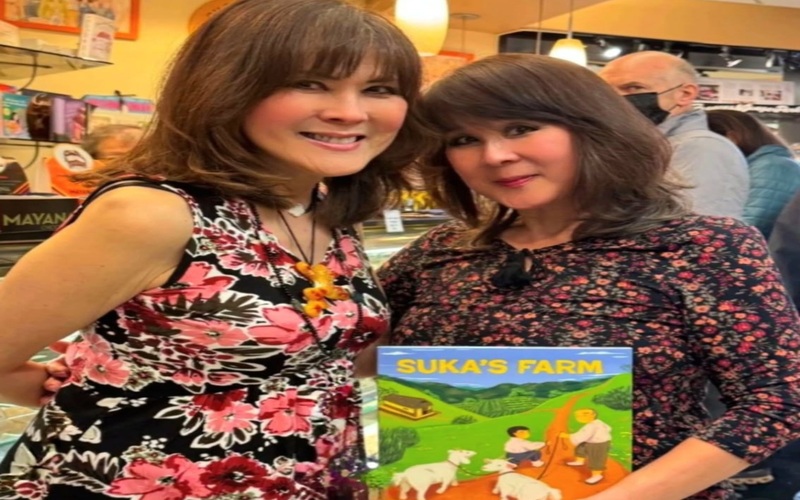

If writing is a solitary journey, collaboration is a joyful celebration of ideas, thoughts, and words. Partnering with Frances is so much fun; it’s like having our own personal editors. We have written ten books together (about our father, our mother, our grandfather among others) and we have never once had a disagreement. Uncanny, right?! But we never actually sit down and write together, either. One of us comes up with the idea and hammers out a draft, then the manuscript goes back and forth with edits and queries via Google chat. Fortunately for us, our vision for our works have always aligned—perhaps it’s in our DNA!

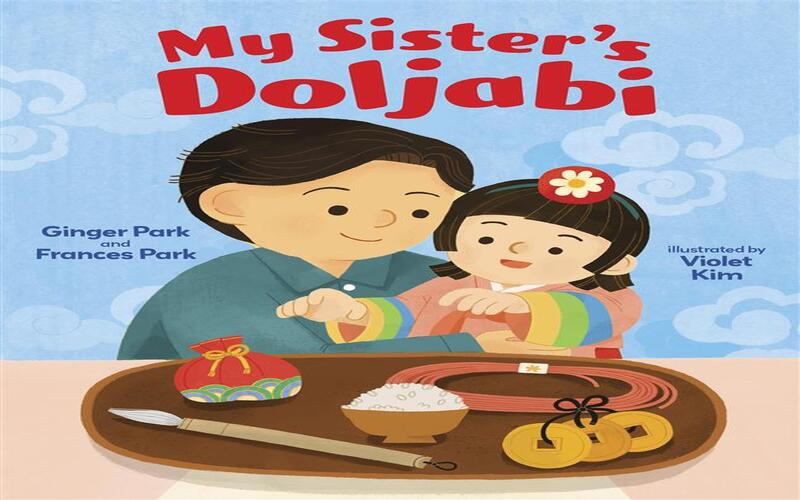

-Your new book, My Sister’s Doljabi, celebrates an important Korean tradition. What made you choose this particular custom as the focus of the story?

While we’ve explored dol in our longer works, it was one of our publishers who asked us if we would consider writing a picture book on the topic. We were thrilled at the opportunity to create a meaningful story around the celebration. My Sister’s Doljabi is told from the perspective of baby Binna’s older brother, Hoon, who is counting down the days to his sister’s first birthday. When he learns the history of dol and why it is such an important milestone birthday, he begins to fret over Binna’s future. When it’s time for the fun doljabi game that predicts a child’s future, Hoon encourages Binna to pick the thread, symbolic of long life. Excitement swirls as Binna’s little hands hover over each item. Which one will she choose? An enthusiastic shoutout to the incredibly talented Violet Kim for her illustrations that bring a luminous visual voice to the story.

-Are there other aspects of Korean culture or life you hope to explore in future books for children

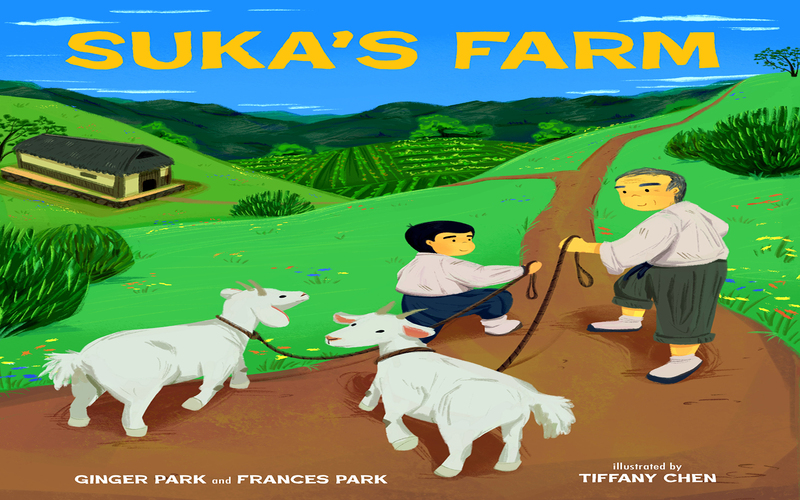

Our picture book, Suka’s Farm, explores our father’s early years as a hungry boy under Japanese rule. It’s a beautiful story of a Korean boy who is hired by a Japanese farmer to tend his goats, and the unlikely friendship that blooms.

I recently completed a picture book manuscript about a Korean girl whose family moves from Los Angeles to Washington, DC during Chuseok; it’s a magical and heartwarming story about finding light in a new home. It’s now with my agent, so we’ll see if she enjoys the story as much as I enjoyed writing it.

-Can you tell us about The Hundred Choices Department Store? What inspired you to write it, and do you have any memorable moments from the writing process?"

My mother had a silver-framed black and white photo of her family sitting on her bedroom dresser. Growing up, I passed by the photo thousands of times never stopping long enough to reflect on the family who perished long ago—they were merely ghosts of my ancestry. But one day, in the wake of my father’s passing, I picked up the photo and gazed at each family member, aching to know their history—how they lived, how they died. Through my mother, discoveries were made, both heartbreaking and eye-opening. Her family owned a small department store in their hometown of Sinuiju, enduring the Japanese occupation and the post-World War Two Russian invasion.

I learned that most of my mother’s family died during wars (Battle of Shanghai, World War Two, the Korean War), and for those who survived, they were left with deep wounds, physically and emotionally. All would be gone before I was born.

The Hundred Choices Department Store is a love letter to my mother’s family. When I started writing the book, my mother was in her late 80s, and I knew this would likely be my last written work in her lifetime. So, the entire process was not only memorable, but emotional. After I completed the manuscript, I handed it over to my mother for her to read. When she was done reading, she clutched the manuscript and brought it to her chest, murmuring, “My family.”

Sadly, my mother passed away eight months before the book’s publication. But I know she would be so proud; even prouder to know that the black and white photo of her family now sits on my bedroom dresser.

-The story touches on themes of identity, migration, and difficult choices. What is the key message you hope readers take away from the book?

Honestly, when an idea pops into my head, I have few expectations—I simply write from the heart. If there is a message in The Hundred Choices Department Store, it is to treasure your freedom. When I embarked on the book, I only knew the privilege that comes with living in the free world. I had to delve deep to tell my family’s story of bondage and oppression, of tragedy and triumph during wartime Korea; these aspects of life were so foreign to me. But knowing all my mother sacrificed for freedom was my guiding force.

The book was also published in Korea under the title Shinuiju Baekseon Department Store. Now in a second printing, the book will soon be released as an audio book. Eomma is beaming in the clouds.

-You’ve received numerous awards in children’s literature. How have these recognitions impacted your work as a writer?

I’m deeply honored that my work has received recognition, but receiving letters from my readers is the greatest award of all.

-Are there any upcoming projects or books you’re currently working on that you can share with us?

I’m currently working on a young adult novel that I’ve deemed a life project. The work might never see the light of day, but I’m compelled to write the story of my mother’s brother who was a Korean rebel during the Japanese occupation. During his short life (he died at 19), he quietly fought for Korean human rights, elevating awareness. My hope is to give voice to his memory.

In this interview, we explored the life of Ginger Park, her Korean-American identity, and her journey in the world of writing—a world that blends heritage and creativity, offering readers stories full of culture and meaning.

How about this article?

- Like3

- Support1

- Amazing0

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0