When I first read Bora Chung’s “Cursed Bunny” about two years ago, my mind was mostly preoccupied with my own youthful concerns—choosing a career path, making decisions about school, and dealing with all the typical worries about an uncertain future. At the time, like many others at that same stage of life, the personal matters felt more real and urgent to me than the collective, and I simply wasn’t ready to engage with the larger societal themes woven deeply into Chung’s work.

Having recently returned to this collection of short stories, I now find myself seeing them through a very different lens, one with a greater awareness for the society conveyed in Chung’s storytelling—our collective fears, the eerie forces shaping our lives and the unsettling tension of a world in constant motion. Through her unique blend of fantasy and horror, Bora Chung becomes a guide, inviting me to explore the deeper troubles that ripple beneath the surface of our contemporary lives, in ways I hadn’t been prepared for before. Her stories haven’t changed—but I have, and with that, so has the way in which they speak to me.

Born in Seoul in 1976 to dentist parents, Bora Chung received her bachelor’s degree from Yonsei University where she double majored in Russian and English Literature. She then completed her graduate studies in the United States, first her master’s degree in Russian and East European Studies at Yale University, followed by her Ph.D. in Slavic Literatures from Indiana University. After returning to Korea, Chung worked as a lecturer at Yonsei University, teaching science fiction as well as Russian language and literature, until 2021 when she resigned to focus on her writing and family. Chung has continued to translate modern works from Russian and Polish into Korean, having recently completed translating Anton Hur’s debut novel “Toward Eternity”, set for publication later this year.

In 2022, her collection of short stories titled “Cursed Bunny”, translated by Anton Hur, was shortlisted for the prestigious International Booker Prize. Now widely accepted as a prominent figure in contemporary Korean literature, her stories combine science fiction, horror, and folklore, often exploring surreal occurrences. In our interview, she discusses the legends influencing her, her writing process and a Korean horror TV series she used to watch with her grandmother, giving some insights she has never before shared publicly.

This interview was conducted in writing via email between April 23 and May 24.

Could you please introduce yourself?

My name is Bora Chung. I write scary stories and translate Russian and Polish literary works to Korean.

How did your interest in writing begin during your childhood?

I never thought I would become a writer. I thought writers all starved and could not make a living. I did read a lot of books, and my parents and teachers liked it and encouraged it. Also, writing, as in logically presenting one’s argument on a topic, was an important subject while I was in school, and it was also very important for the university entrance exam, so I studied writing from that point of view. I was interested in reading newspaper articles and opinions. It started as a training for that writing subject in school, but I enjoyed it.

Do you remember the first story or tale that scared you?

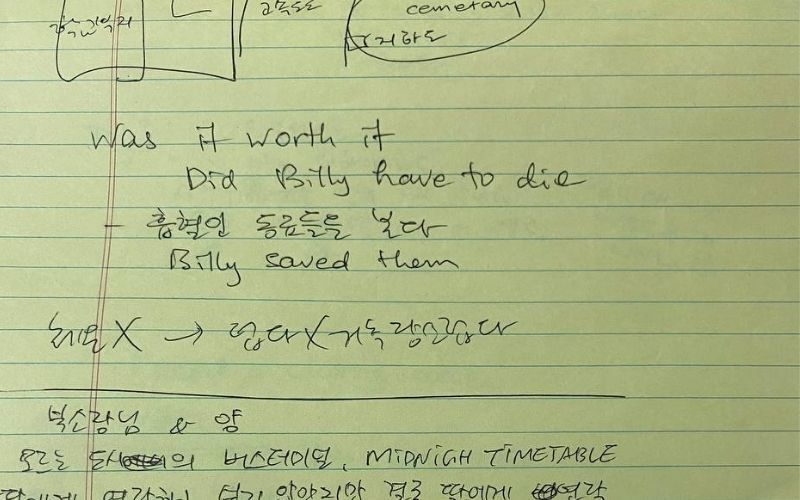

In the 1980s, Korea Broadcasting System aired a hugely popular TV show called “The Hometown of Legends”, which introduced small towns across Korea alongside their unique stories—intended perhaps to boost tourism. However, most of these stories ended up being ghost tales. My grandmother, who lived with us at the time, loved this show, and I used to watch it with her every Saturday night.

One episode that stands out in my memory was called “Give Me Back My Leg.” The story is about a woman whose husband is gravely ill. A Buddhist monk, a common figure in Korean legends, tells her that in order to cure him, she must go to the village cemetery at night and cut off a leg from a dead body. She’s then supposed to make a soup out of it and feed it to her husband. So, the woman, armed with a knife, ventures into the cemetery on a stormy night (rain, thunder, lightning—everything dramatic). She finds a body that hasn’t been buried yet and cuts off the leg. As she picks it up and turns to leave, the body suddenly springs to life and screams, “Give me back my leg!”—and I swear, I almost died of fear at that moment.

The woman runs back home, but the body (or the ghost?) chases her. Just as it’s about to catch her, the rooster crows, the sun rises, and the body returns to being dead. The woman brews the leg, and in the morning, it turns out to be not a human leg but a thousand-year-old ginseng root, which cures her husband. A happy ending after all!

Some say that telling fantastical or scary stories to children prepares them to protect themselves from real-life dangers—not directly, but through metaphor, fear, and imagination. As a writer and activist who challenges the world’s injustices, how do you see your use of horror, sci-fi, and speculative fiction as a way of doing something similar for adults—by engaging with the same storytelling instincts that shaped how we understood the world as children?

I think there is a certain pleasure in exploring our own feelings, especially strong and unusual feelings such as fear. Stories help us process these feelings because there is always a beginning and an ending. Fantastical or scary stories do help us understand ourselves and our own feelings, our own imaginations and our own inner selves as much as they help us understand the outside world.

Are there any childhood stories or fairy tales that still inspire you—perhaps ones that shaped your view of the world through fantasy and planted ideas in your subconscious?

I love the story about the magic flute named “Man Pa Shik Jok” which means “the flute that puts 10,000 waves to sleep.” Legend has it that the good dragon of the East Sea told the king of Shilla to cut down a specific magical bamboo tree on a floating island on the East Sea to make this flute and save the nation. When they played the flute, the storm and typhoon cleared, heavy waves calmed down, plagues disappeared, and enemy soldiers retreated. I thought about this flute a lot during the COVID pandemic.

Could you tell us about the very first story or piece that you wrote—maybe one from your childhood that you still remember?

The first story I wrote was “The Head” from the collection “Cursed Bunny.” It was written for a school literary contest while I was in college. Like I said, I never thought I would become much of a writer, so I saw it as a one-time thing that I could try out while I was still a student. Then I won the award and got the cash prize. I was very happy.

What kinds of things inspire you and spark your creativity while you are preparing to write?

I habitually gather material from everyday life. I imagine things like haunted city buses—what would the passengers say to the ghost? Or flying bicycles—would the government try to regulate them? Maybe even issue driver’s licenses? I also think about cursing bad people in creative ways. Sometimes I see unusual sights, like a Catholic nun driving a giant cargo truck. I try to remember these moments and use them in my stories later.

What was your reason for choosing the title “Cursed Bunny” for this book, given that it is the first story in the book?

Actually, it wasn’t me, but my publisher, who chose the title. He said it needed to be searchable, meaning it should appear first when someone looks it up online. Titles like “The Head” or “The Snare” wouldn’t work, since the book would get buried in search results. “Cursed Bunny”, on the other hand, is such an unusual combination, even in Korean (or any language, really), that it almost always comes up first. It was purely a marketing decision.

In most of the stories in the book “Cursed Bunny,” we, the readers, might not fully understand what is happening at first, but in that very moment, we feel like it resonates with us at a much deeper level. When we don’t fully grasp something, we tend to compare it to our own knowledge, experiences, and the fears, wrongdoings, and injustices we have witnessed in the world. Perhaps this is why your stories are so striking—from the moment we start reading, we see our own journey reflected in the character’s journey. All the evil we have ever witnessed comes to mind, and we find ourselves wondering, “will the character experience this as well?” What are your thoughts on this?

Once, at a book event, a teenage reader told me she enjoyed my stories because they were “spicy,” but sometimes she could not understand the characters’ emotions—probably because she did not relate to the underlying societal trauma. I was deeply relieved. I do not want my readers to know societal trauma. I want them all to live safe, happy, and slightly boring lives. It would be best if they only enjoy the stories because they like “spicy” stories.

On the other hand, many of my activist friends—and my husband, who has been an activist for more than 30 years—told me that “The Scar” resonated with them the most. I am glad they like it, but at the same time it makes me sad that this fantastical, imaginary trauma has something in common with the real-life experiences of these people I know and love.

Why a bunny? Does the rabbit hold any personal or symbolic meaning for you?

I am part of a writers’ group for an internet magazine called “Mirror” (mirrorzine.kr). We update this webzine once a month, publishing our stories on the internet for free, and during the summer we gather our stories and publish them together as a paper book. At the end of 2015, we were discussing when to publish in 2016 and under what topic or title. Somebody suggested the Asian zodiac, and everybody liked the idea. The glamorous animals—dragon, tiger, horse—were taken instantly. Familiar animals such as the dog, rooster, snake, and rat were all taken subsequently. The discussion was online, and when I logged in, there were only the rabbit and the sheep left. I do not know anything about sheep, but we had two rabbits in my elementary school zoo, and I still have a vague memory of them always eating, so I chose the rabbit. I do not have a special interest in rabbits; I was just late to join the discussion.

As both a writer and a translator, how do you feel when your book is translated into foreign languages, such as Turkish, which you don’t speak yourself?

I trust my translator completely. There’s no hidden message. The reader has the full, absolute right to read any story (including mine) as they wish. My translator is my first reader in any given language, and I hope they enjoy the reading. I trust that my translator will know the best way to present the story for that culture, because conveying the story properly within the reader’s cultural and societal context is the most important thing. As for “Cursed Bunny” being translated into Turkish, I never imagined this! I’m still so excited every time I think about it. The reception has been incredibly enthusiastic, and I am both grateful and still surprised.

How is your writing process like? Do you like to share a story with others while you are still working on it, or you prefer to show it to them only once you have finalized writing it?

I prefer waiting until the story has taken some concrete shape. Otherwise, I feel that the story might “crumble” while it’s still “unripe.” I like writing on paper with my favorite pen to see how my ideas look like, but even then I wait until I am certain the ideas are concrete enough to appear on paper, even if I am the only one who is going to see them.

What has been the most unexpected yet constructive feedback you have ever received? How do you handle it when someone finds a draft of your story uninspiring or doesn’t like it?

When I wrote the first draft of “The Head” some 27 years ago (oh wow! It’s been a long time!), my sister read it and said: “This is boring.” Back then I tried writing a realistic story, so I described the woman in the bathroom being shocked and disgusted, and running out of the bathroom, etc., but then I got stuck. I realized I myself was bored with my description, so I deleted everything and started again, this time going in the opposite direction. The woman doesn’t react, the conversation with “the head” sounds very unnatural in the original Korean, and “the head” speaks a lot more. And then the story wrote itself until the end.

Since that time, whenever I feel stuck, I go back to the most problematic part and direct the story to the opposite direction from there—usually the more fantastic the better. It’s been working well!

Getting shortlisted for the prestigious International Booker Prize in 2022, what did this recognition mean to you personally and professionally?

I was dazed and confused the whole time. It changed my life completely. I had been a university lecturer for 12 years prior to that and I had quit that job only because my husband’s cancer had come back. I was imagining that I would take care of my husband through his treatment and then go back to teaching.

Then the International Booker Prize nomination happened and everybody around me was so happy. My husband wanted to go to London, UK for the ceremony and I was extremely worried about his health. I was so scared for him the whole time, but I also realized I could be a full-time writer and make a living now, and that way I could stay home and take care of him better. In short, as a writer it was a great honor, a completely unexpected one. As a person it was a shock to me. I still don’t understand what happened.

Lastly, what advice would you give to aspiring writers?

Take care of yourself. Maintain your health and do whatever makes you happy. Take good care of your eyes and your joints, especially. If writing doesn’t make you happy any longer, don’t obsess over it. Your stories will come back to you and your inspiration will hit you when you are the least expecting. You have to be healthy and well enough to grab the opportunity when it comes.

How about this article?

- Like6

- Support3

- Amazing4

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful1