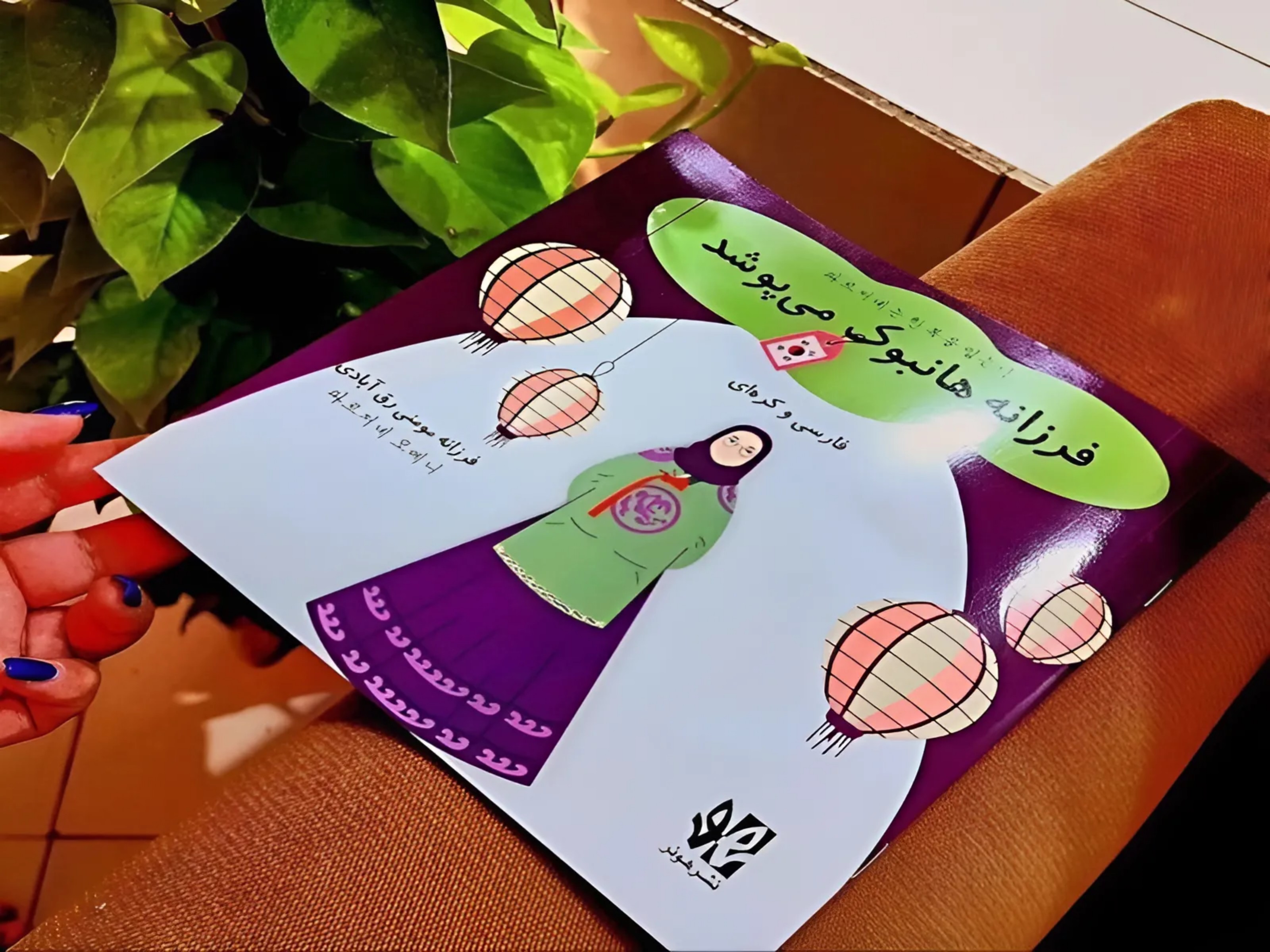

The translation of Korean texts in Iran, such as K-Pop and K-Drama, is one of the fascinating phenomena that has captured the interest of Korean culture enthusiasts these days. In addition, one of the fascinating phenomena that has attracted the attention of Korean culture enthusiasts in Iran is the publication of books in Korean or Persian and Korean. Like the book "Farzaneh Hanbok Wears," written for children's age categories and published with an attractive illustration.

In addition to the beautiful illustration, the attractive content of this book in Korean also greatly impressed us. Therefore, we tried to provide an interview with Farzaneh Momeni, the author of the book Farzaneh Wears Hanbok, and the Korean language translator.

To gain deeper insights into her work, we interviewed her on October 17, 2024, at Tehran's Shifteh mansion. We are pleased to share this engaging conversation with you.

Could you share with us some information about yourself and your works?

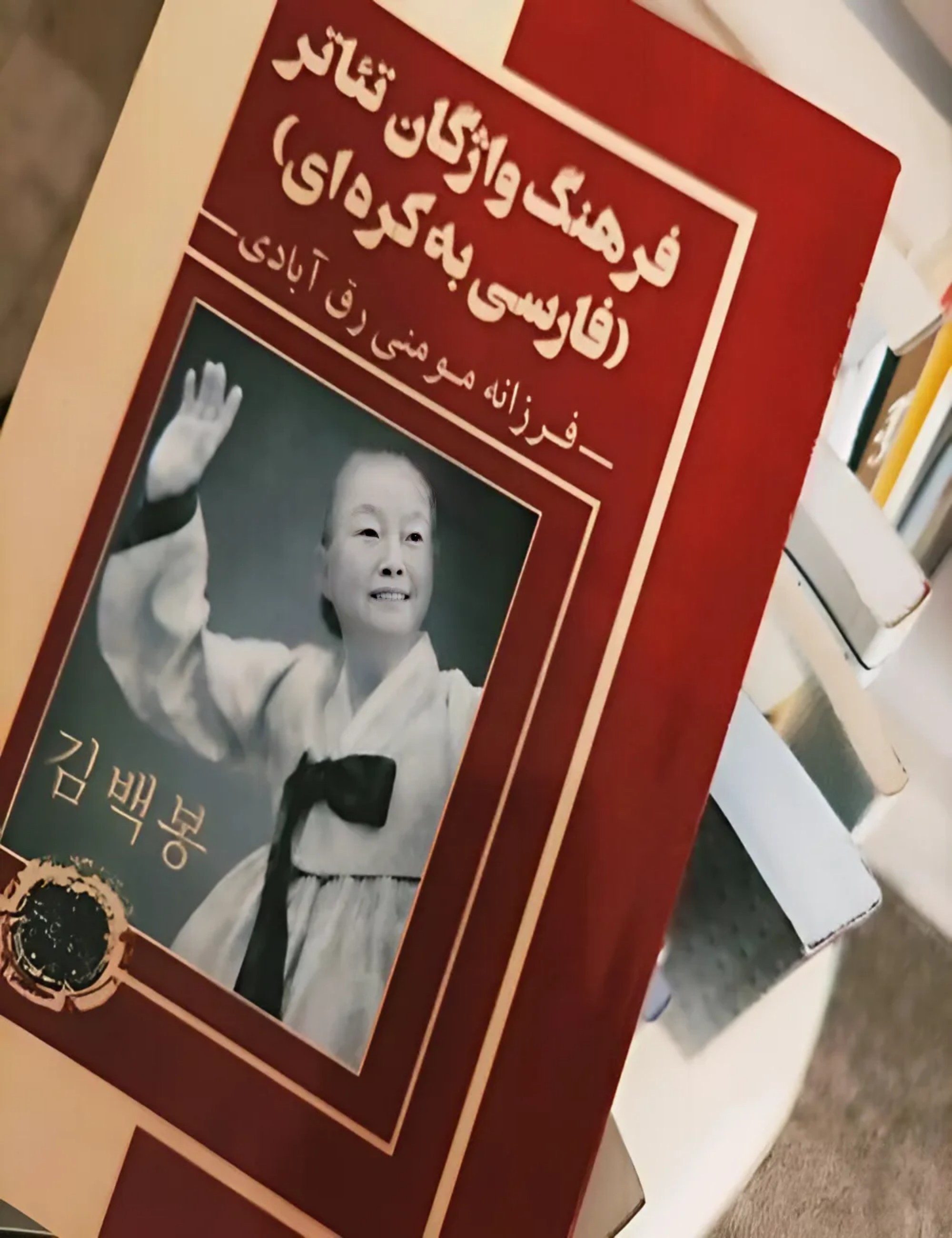

My name is Farzaneh Momeni Raghabadi, and I was born on October 24, 1990, in Kerman, Iran. I hold a bachelor's degree in acting and directing from the Art University of Tehran, and I am currently pursuing a master's degree in acting at the University of Tehran. In addition to being fluent in Korean, I am also proficient in English. My publications to date encompass the translation and original authorship of a few books: *A Dictionary of Theater Vocabulary (Persian to Korean)*, *An Introduction to the Art of Pansori with Five Texts*, *Juche Poetry*, *Korean Folk Performing Arts (Relying on Buddhism, Shamanism, and Other Religions from the 13th to the 19th Century)*, *Sweet Korean Tales*, and *Farzaneh Wears Hanbok*.

I have been fascinated by Asian television series since my childhood, particularly those from Korea and China. When I was twelve, a popular Korean series, Hong Gil Dong (known as the Korean Robin Hood in Iran and other parts of the world), aired. One of the actors, Jang Keun-suk, caught my attention. Upon researching him online, I discovered that he was also a singer. My initial exposure to K-pop was through this artist's music videos, leading me to explore other videos and performances available at that time. The first Korean pop group I observed performing was Orange Caramel, a subgroup of After School. Their unique performance style had a significant influence on me. I was also very interested in Crayon Pop. The music videos I watched all had Korean subtitles, and this inspired me to learn Korean. Despite the limited resources available online, I found a few materials and gradually learned the Korean alphabet. Watching K-pop music videos with Korean subtitles greatly contributed to my progress in learning the language.

When I was 18, I was a dedicated student in the mathematics major, but I also had a strong passion for art. I spent my free time writing stories and novels. After achieving a high rank in my entrance exams, I made up my mind to focus my future on learning and creating works of art. During my time at university, I had the privilege of learning from three professors who helped me discover my interest in oriental theater: Professor Zargar, Agha Abbasi, and Nasser Bakht. Through their classes, I was able to appreciate the beauty of oriental performing arts and recognize their similarities to Iranian performing arts. Among these professors, Professor Agha Abbasi provided fascinating insights into Naqali in his classes. Simultaneously, I began studying Korean performing arts and discovered that Koreans have a similar performing art called Pansori. This interest in Pansori led me to seek various sources on the subject. I then spent about a year translating all discoverable PDFs pertaining to the topic, intending to produce a documentary. I shared this idea with one of my professors, who provided substantial support. Eventually, I successfully produced and published the documentary on YouTube.

This esteemed professor suggested that I write an article about Pansori, if no such article had been written. Upon checking, however, I discovered that another professor had already written on the topic. Discussing this with our professor, he encouraged me to turn my research on Pansori into a book. In search of Pansori's text and stories, I could not find any written sources in Persian. Consequently, I resorted to watching Pansori performances on YouTube with subtitles, translating them to understand that the art form has a fixed text. I translated these subtitles to include the captivating Pansori story within my book. And eventually, with the support of our professor, I successfully published my book about Pansori.

Among the works you have written or translated, which one would you most recommend to others to read?

I myself like the book Sweet Korean Stories the most, and I recommend it to others to read.

Have you ever considered staging an oriental performance?

I have always been interested in this endeavor and truly desired to pursue it. In Kerman, we even established a theater group, and I translated the text of the legend of Chunhyang for a performance. Unfortunately, unforeseen obstacles hindered the staging of the play. Nevertheless, my interest in this work has remained unwavering, and I am contemplating the possibility of staging such a production in the future.

What are the differences between Iranian and Korean performing arts that have attracted your attention the most?

One of the important things is their success in doing teamwork in a correct and appropriate way, which I rarely see in Iran.

Often, the texts that a translator translates follow a specific line that indicates the translator's interest in translating this type of text. What types of texts do you choose to translate the most, and what is it about those texts that attracts you?

I am very interested in fairy tales and legends, and most of the texts I have translated have usually been of this type or have been related to the performing arts in some way. Fairy tales are fascinating to me because they come from a place where people have a need that they don't have an answer to, and for that reason, they create a legend that somehow answers the question in their mind. For example, the Korean people did not know how the sun and the moon came into being, and that is probably why they created the legend of the Brother and sister who became the Sun and Moon.

The story of this legend is that the Sun and the Moon are two children whose mother has gone to find food for them. Like the story of Shangul and Mangul of the Iranians, a wolf comes to them when the children's mother is not there. In the continuation of this Korean story, a tiger comes to these two children, and the children go to the top of a tree to escape from the wolf, and a rope comes to them from the sky. The two children take the rope and go to the sky, and one of them becomes the Sun and the other the Moon.

I have a strange interest in fairy tales in general, and everything I've ever liked has had something to do with fairy tales. For example, I remember when I first got into Korean music videos, a member of the group Orange Caramel named Lizzy released a music video called "Not an Easy Girl" that I loved, and later I found out that the story was the same as Chunhyang's tale.

Another aspect I appreciate about Korean fairy tales is that the characters are typically straightforward and familiar to all readers, unlike Greek myths, which often feature complex characters requiring deep analysis. Additionally, I am drawn to the fact that these tales have been passed down orally through generations, representing a cherished ancestral heritage of the nation.

Could you elaborate on what you perceive as lacking in our artistic productions, particularly within the theatrical sphere?

I believe that strong group collaboration is a crucial element lacking in Iran, and another aspect is that our theater does not adequately address love and genuine emotions. We primarily focus on Greek theater, which centers on moral vices like betrayal, whereas Korean legends, such as the story of Chunhyang, revolve around the theme of love.

What do you think the Iranian art community should learn from East Asia and Eastern art?

An interesting point that has occupied my mind since childhood is that when Koreans have a specific indigenous art form, no matter how low its level is, they care about it and invest in it so much and try to improve it to the best quality level. I think if we also invest in what we have and spend time on it, we can make significant progress. This is something that we should apply not only in art but also in our own lives and do it in the best way possible in everything we do with patience and effort.

Do you think it is possible for Iran and Korea to create a joint work in the form of a play, film, or any other artistic form that draws from the history, culture, and literature of both countries?

I think it is quite possible. Just as the Koreans performed Kushnameh several times as a co-production in Iran (once in Isfahan and at the Milad Tower in Tehran), it is still possible for such works to be co-produced.

What is your concern in life and the artistic work you do?

One is to be happy and peaceful and to convey these two to others, which is the most important thing to me. I always want someone to read my work and have a smile on their face and joy in their heart. I have always wanted to bring knowledge and something that did not exist, because I was very bothered by the lack of resources about Korea.

How about this article?

- Like30

- Support0

- Amazing2

- Sad0

- Curious0

- Insightful0